Where this game shines is in the way character is conveyed. You’re playing a puzzle game, so there’s a puzzle in each level where you have to get the blocks (the characters) from A to B. There’s usually only really one or two ways to do that, and those solutions rely on the characters interacting with each other in certain ways.

For example (and I’m writing this from memory), one of the early levels involves Thomas (the red rectangle above) and Chris (a grumpy squat brown block). Each character has different abilities: Thomas can jump about twice as high as Chris, but Chris is smaller and can fit through little gaps.

This particular level was basically a long staircase with quite high steps. Thomas can just happily jump up the stairs and get to his end-point, but Chris can’t jump high enough to get up the stairs. In order to solve the puzzle, Thomas has to come back down the stairs, and Chris has to use him as a stepping stone – Chris jumps on top of Thomas, and then onto the stair.

In this moment, there’s a certain distribution of power between Chris and Thomas. Thomas can go to his end-point, but Chris can’t get there without the help of Thomas. Chris is reliant on Thomas to get to where he needs to be. Because Thomas is optimistic and excited, while Chris is grumpy and cynical, one can imagine Chris’s frustration at his dependence. Through the combination of gameplay and Merchant’s narration, the characters deepen and relationships evolve.

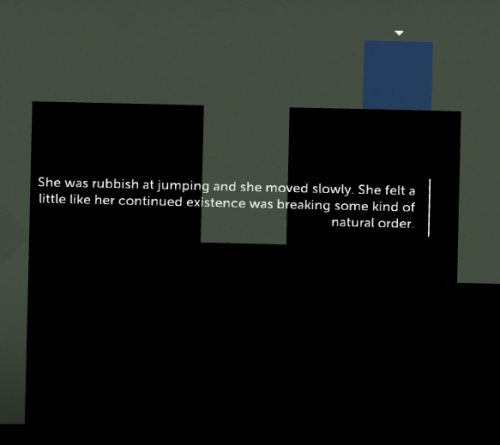

Another example would be Claire, a large blue block who has self-esteem issues and very limited movement capability. Her ability to jump is extremely poor, and she’s quite slow compared to all the other characters.

In the introduction to Claire, we discover that she has the ability to float in water without ‘dying’. Every other block is destroyed upon contact with the water – Claire is the only one able to enter into the water unproblematically. As she explores this unique capacity, her self-confidence grows, especially as she is key to solving several different puzzles.

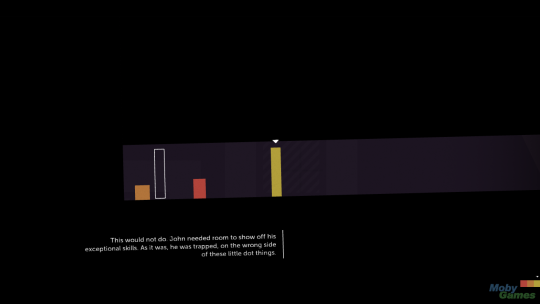

A third character introduced is John. John is the tallest character, and is arrogant and flamboyant. He has the second-highest jump ability of all the characters, coming second only to Sarah, who is able to double-jump.

Although John is much more powerful in terms of jumping than Chris or Thomas (or Claire), he is portrayed as something of an arrogant nuisance. For example, in the level shown above, his height is actually the locus of the puzzle. He’s in a limited environment, where, in terms of power distribution, his height becomes counter-productive, in much the same way as Chris’s inability to jump very high creates the problem which needs to be solved.

However, there is a distinction between the difficulty created by Chris and the difficulty created by John. Where Chris is inconvenient because he lacks certain characteristics, John is inconvenient because he possesses certain characteristics. When this inconvenience is coupled with John’s evident pride and ability, he starts to seem – to my mind, at any rate – something of a nuisance. I read John as a nuisance because his attributes (rather than his lack of attributes) make him a nuisance on a ludic level. I’m willing to feel sorry for Chris, but John thinks he’s great when he’s actually a nuisance, so I’m much less well inclined towards him.

A quick aside – this is probably the most vulnerable point of my argument. I’m looking at the gameplay elements that contribute to John’s character and drawing an emotional character judgement out of that. Other players might draw a different character judgement from the same set of gameplay elements, and that’s entirely reasonable. The weakness, such as it is, is that the rest of my argument relies on my interpretation of John as a fucking nuisance.

Okay: so John’s a nuisance. Here’s the question: is John actually a nuisance, or does he just seem like a nuisance because of the situations he’s put into? It’s theoretically possible for the game to revolve around puzzles where John is the lynch-pin centerpiece to solving everything. John doesn’t need to be positioned in gameplay situations where his qualities make him a nuisance – he’s been intentionally set in these situations that make him out to be like that. Why? Because that’s how the game works – it builds character by putting these blocks in contrived circumstances that force them to relate in certain ways.

What we’re heading towards is a discussion of the way in which the environment shapes character in this game. We only perceive the characters in the ways that we do because they’re in a set of environments which dictates their actions. We could actually go as far as to say that the environment dictates the character development (at least on a ludic level).

So in short, we’re saying that Thomas Was Alone is a bit contrived, in that the level design forces you to solve the puzzle in a certain way (and therefore play out the power relations in a certain way, and therefore develop character in a certain way). Most of the time we don’t mind that contrivance, because we’re so wrapped up in these characters that we’re just enjoying the story. However, the contrivance (for me) becomes more pronounced with characters like John, because even though I find him frustrating (on a ludic level) I feel like it’s not really his fault. That’s just the way the game is set up to be played.

This is where the really hefty theory starts coming in. There’s a guy called Miguel Sicart, who works on ethics and video games. He’s got an article called “Against Procedurality” (http://gamestudies.org/1103/articles/sicart_ap), where his basic contention is that games like Thomas Was Alone are bad insofar as they rob players of the opportunity to make meaningful contributions to the way stories develop. He argues that we’re not playing these games so much as being played by them – which to some degree is true. In Thomas Was Alone, we play out the pre-arranged set of solutions that the designers intended, and that kinda mutes the creative nature of play – at least for us as players. We can still be creative in hunting for the solution to the puzzle, but there is a solution, and there is a correct set of steps which need to be carried out.

Although I agree with Sicart’s analysis of how games like Thomas Was Alone work, I’m not necessarily convinced that it’s a bad thing. Thomas Was Alone, for all its other faults, is an incredibly focused character-driven experience, and even though there are little signs of contrivance, I’m mostly willing to overlook them just for the joy of the experience. The point I’m making is that you don’t get tightly crafted narrative experience in Minecraft, you get a bunch of fucking around and a cool highlight reel. That’s fine, for what it is, but I think – and this is my main contention – that it doesn’t work for making well-built stories.

[…] is the interesting difference with something like Thomas Was Alone, which I’ve written about before. I won’t give any background – you can read the other article, if you like – but […]

LikeLike