Florence is an interactive narrative game published in 2018 by Annapurna Interactive. Developed by Australian game developer Ken Wong, Florence follows the romance and breakup of a young couple living in Melbourne. The game was originally developed for mobile, so there are a bunch of very tactile mobile-esque interactions – you have to shake a polaroid to develop the image, and you ‘draw’ pictures by rubbing over the screen, like it’s a digital scratch card. These different types of interactivity flag the game’s broader interest in material form. Florence is interested in stuff. When Florence goes over to visit her new boyfriend Krish for the first time, there’s a sequence where you help Krish hastily clean his room. Socks get tidied, the cello goes back into the case, the bed gets made – it’s a really cute ‘before and after’, and you get to know the details of Krish’s life in a deeper way than if you just glanced at his clean room. For example, when Krish cleans up the stack of dirty dishes on the chest of drawers next to his bed, he also hides his action figure and replaces it with a pot plant. He’s not just cleaning in this sequence – he’s tinkering with how he presents his identity, with how he wants this girl to perceive him.

Florence uses stuff really consistently to explore the relationship between Krish and Florence. When Florence comes over, Krish’s bedroom shifts from being a private, for-him space to being a public or at least shared environment. The ‘before’ image on the left shows how Krish is to himself. His bedroom is his private sanctuary: he has the freedom to be messy, to be nerdy, to not make his bed. We see how he is to himself. When Florence comes over, she’s still a new person in his life. There are proprieties to observe. Krish therefore tidies up, making the space presentable – that is, making it align with how he presents or performs his identity in more public, shared environments. He puts away some of the more private parts of his life – his mess, his nerdy toys. In a sense he puts himself away. Their relationship then develops as Florence uncovers the things he’s concealed. Krish is acting all cool, and pretending like he’s super tidy all of the time, and Florence spots an Academy of Music application poking out from under the bed. She undoes some of his hasty tidying, peeling back the polite façade and discovering a genuine passion. She doesn’t learn everything at once – the empty can stays buried under the bed, as does the screwed up ball of paper, and other crumbs and boxes. There will be more to unpack in the future, as their relationship develops. But this insight is enough to propel them into the next part of their story: Florence encourages Krish to go to the Academy and pursue his passion.

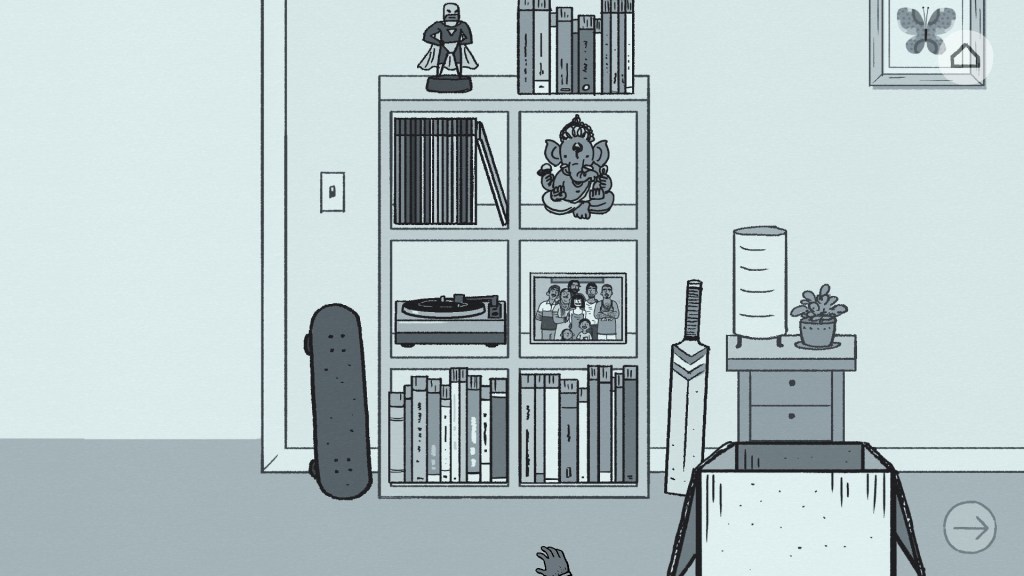

The dynamic here is between stuff hidden and revealed, stashed and found. It’s stuff made present and absent. The same dynamic continues throughout the rest of the game. When Krish moves in with Florence, you have to help them integrate their belongings. Krish turns up with boxes full of stuff, and you decide what comes off Florence’s shelves to go into storage, and what gets put in their place. You decide how to balance and divide their belongings. What goes on the shelf? What stays in the box? How much of each person’s stuff should be displayed? You rearrange the shelves as metonymy for the couple rearranging their lives. You make space on the shelves as they make room for each other in their lives. There’s negotiation between cultures, between different personalities. Krish turns up with a spice box and a mortar and pestle. He has a coffee plunger where Florence has a teapot. What stays? What goes? They also find points of overlap: living in Australia, they both have a toaster and jars of Vegemite. These are the types of practical negotiations that happen when two people move in together, but they also symbolize or evoke the broader negotiations that are part of every escalating relationship. More and more, they find themselves asking: how do we bring these parts of ourselves together?

Later on, when Florence and Krish break up, the same process is carried out in reverse as they disentangle their belongings. You decide what to take off the shelf and put into Krish’s box. Do you try and isolate the things that originally belonged to Krish? Does he take anything extra with him? Some things are obvious, but not all the items can be cleanly divided. In one room, there’s a photo of Florence surrounded by Krish’s family. Who gets to keep that? Neither of them brought it into the relationship – it’s something that’s been mutually produced during their time together. Both keeping it and discarding it introduce types of gap. If Krish keeps it, he has a memento of a relationship in his life that isn’t there any more. If he leaves it behind, he foregoes a memory of his family. The lives of this couple can’t be fully disentangled. They have been, and will continue to be, a part of each other. Also – just the final little gut punch – by this stage, Krish has his little action figure back on the shelf. That secret part has been uncovered, and now it’s being concealed again. Back in the box, dollar store Superman.

Florence operates around the principle of presence and absence. Things are hidden and displayed, put in place and taken away. The underlying question, through all of it, is what’s left when something’s gone? Whether it’s items going into storage or Krish jamming things under his bed – what does it mean when something’s not there any more? And what does that say about the value it had in the first place? The game explores this question in all the little sequences we’ve discussed, but most of all through its central relationship. At the start of the game, Florence is living a dull, routine life. She ticks the boxes and does her job, but everything is grey and boring. Krish brings a flash of colour into her life. Florence is swept along on a shock of yellow listening to his music. For a time, she finds meaning in that relationship. She’s sad once it ends, but it’s not the end of meaning. She moves on, finds meaning elsewhere. Some time after the break up, Florence finds a set of paints that Krish had bought her. She takes up painting, returning to something she’d always wanted to do. She finds meaning in it. Eventually she’s successful – sales, gallery openings, a full-blown business. It’s not these things in themselves, though, you understand. It’s how Florence finds meaning in them. They had meaning while they were around, Florence suggests, and if they ever go, they’ll carry meaning still.

[…] Florence: On Stuff in Video Games | Death is a Whale James contemplates the representational power of things. […]

LikeLike

Lovely thoughts. In couples’ counseling one of the things that came up was that there was basically nothing in our house that my wife chose to put there, and it really highlighted how much she didn’t feel permission to be heard or influence the direction of our family, so this really resonated with me and I’m glad I read it.

LikeLike