When I started writing here, I had a bunch of things I wanted to discuss. I would write essays over the top of each other, queueing them up weeks or sometimes even months in advance. I just had a lot going on. That’s not really the pace any more. My work now is slower, deeper. The rhythms have changed. It’s been eight years, you know, most of my twenties – I still love what I’m doing, but I’m not doing it with the same frantic energy. Anyway, I had a couple of different essays jostling for position this week. They both wanted to be written first. There was a time I would have tried to do both of them at once. We’ll keep to current practice: first cab off the rank.

Night Call is a 2019 mystery game where you play a taxi driver working in Paris in the modern day. You take jobs driving people from place to place, and you have to listen to their conversations and try and gather evidence to identify a serial killer stalking the city. The serial killer thing is probably not the most interesting part of the pitch – really Night Call falls in with games like Papers, Please or We. The Revolution, or Strange Horticulture, or any of those other games that sets out to explore a society through the lens of labour. You play out a day in someone’s life, learning about society not through collectible audio files but from the bottom up, through incidental encounters with normal people. You learn about the world through the way people treat you, and through the way your job makes you treat them. In Night Call, you’re a cabbie. You work in the service industry. You provide a logistical service, transporting people from place to place, and also an interpersonal service. You listen to their problems, bear witness to their doubts. People tell you things. A lesbian couple ask for your opinion on a sperm donor they’ve just met. A lady in her mid-forties is anxious about how her relationship with a younger man is perceived. You serve as a confidant, an advisor. It all puts you in a strong position to be fishing about for evidence on serial killers.

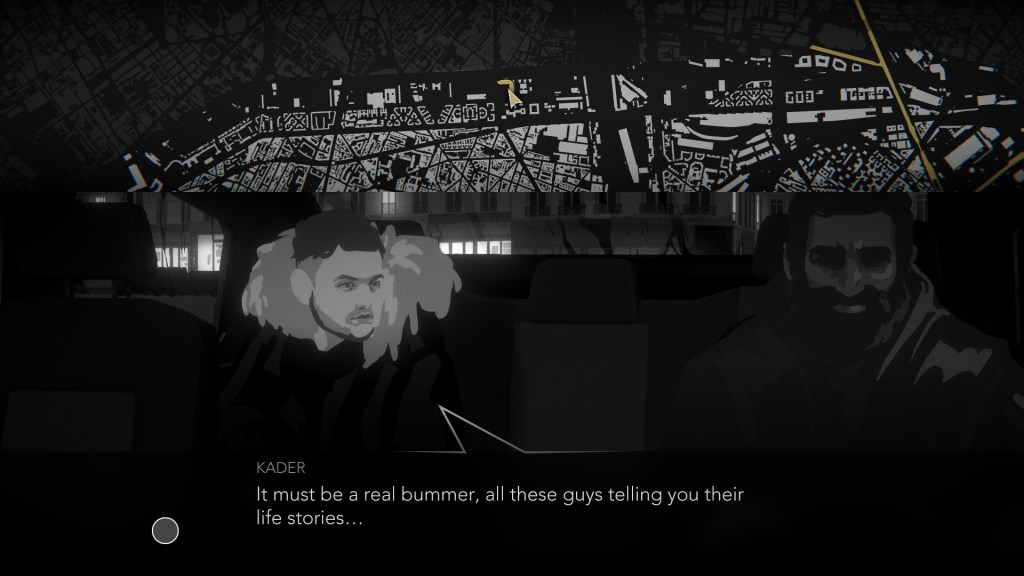

Night Call is also deeply concerned with issues of class and race, with the ongoing effects of colonialism. You play an Arabic immigrant, working the night shift to scrape a living. You make your wages, and then pay out the cost of petrol and fees, and the balance never quite works in your favour. You observe instances of violence and police harassment. One character, Kader Bergaoui, calls for a taxi, and when you arrive you find him surrounded by six Parisian cops. He has a copy of The Count of Monte Cristo, and they want to know who he stole it from. They don’t believe it belongs to him. I could be wrong, but I’m pretty sure Kader is Algerian, or an immigrant from some other place colonized by France. In Paris, he’s looked down on as a second-class citizen. The unwelcome attention from the cops is a reminder of his outsider status. The Count is part of French culture: by insisting that he stole it, the cops imply that he’s not really French, that the nation’s cultural heritage doesn’t truly belong to him – can’t ever belong to him. It’s not just a matter of racial profiling, assuming that he stole the book because he’s foreign. It’s challenging his right to access French identity. He must have stolen it. He must have come to possess it by illegitimate means.

Elsewhere a British customer unloads her guilt about voting for Brexit, despite having a European husband. She didn’t know his rights would be threatened, she tells you. She didn’t know how bad it would all get. The sequence becomes confessional. She reaches out for absolution from her Arabic taxi driver, recognising in him the same marginalized status that now threatens her loved ones. Absolution becomes part of the commercial exchange. The woman pays you for a ride, and also pays you to make her feel better, to alleviate her sense of guilt. She confesses her sins to you and walks away feeling a little lighter. She uses the dynamic of a service industry role to purchase peace of mind from a marginalized person so that she doesn’t have to feel bad about the ongoing suffering and struggle that makes up his daily existence (and the ways in which she has made that struggle harder). She votes for Brexit, and then apologises to an Arabic cabbie in Paris so that she doesn’t have to feel bad about the economic and political consequences of her decision. It’s a masterful study in privilege and wealth. I don’t remember whether she tips.

In addition to these political concerns, Night Call also speaks about isolation under capitalism. The cabbie’s relationship to the people around him is entirely dictated by labour. He connects with people only as long as he’s working for them, only as long as he’s driving them where they need to go. The social dynamic is governed by the economic dimension. It’s intimate, but temporary, and bound by the norms and expectations of paid employment. Once the job is done, they leave, and you might never see them again. Economics in Night Call condition and shape the nature of human connection. Any relationship takes place within the constraints of that service industry framework. It’s not real connection – it’s a facsimile, a simulacrum, bought and paid for over the length of the drive. That’s what you do in the service industry. You give your customers the appearance of intimacy without imposing the burden of commitment. And at the end of the drive they get out of the car and make their way into the black, alienated night.

[…] about before, at length – with Niebuhr on labour and the middle class, with Sagebrush and Night Call, with Romano Guardini‘s comment that the modern techniques of labour “tend to treat […]

LikeLike