Here’s a funny little thing. When you’re communicating (in any medium, really), we have ways to set hierarchies around the information being shared. It’s a way of creating emphasis and focus. It helps organise the information – it ranks or shapes the parts of the message. Sometimes it’s things like dividing a book up into chapters. That division tells you that each chapter is a separate sub-unit within the greater whole. Chapters have their own narrative arc – they have beginnings, middle, and end, and they pace themselves within that structure for effect. I mean – let me just grab a book off the shelf. In Furies of Calderon, the first book in Jim Butcher’s Codex Alera (think Romans with Pokemon), Chapter Thirteen ends like this:

“Odiana asked, ‘And if they know too much?’

Fidelias glanced at his riding gloves and flicked a drying spot of blood from one of them. ‘We make sure they stay quiet.'”

That’s the final sentence of the chapter. It’s conclusive – it has a sense of weight and portent. It’s a comment followed by a long silence, by the gap between chapters. These two are going to kill anyone who knows too much. Whoever that is, they’d better watch out! The lights go down, the scene changes, and we’re left with that lingering sense of threat. It’s a fairly blunt sort of example, and the sort of thing Butcher is known for. It’s a key part of his style. For comparison, the end of chapter 16 of Summer Knight, book four in his Dresden Files series, reads:

“‘Please,’ she whispered. ‘Oh, God, please help me.'”

The guy enjoys dramatic, pulpy chapter endings. It’s just his thing. Of course, we use these sorts of hierarchies outside of fiction paperbacks too – obviously they’re part of many non-fiction texts. As with Butcher, hierarchies in non-fiction are about flow. Scientific papers might use footnotes or endnotes, either for citing sources or for making little asides that don’t necessarily fit into the main body of the text. Editors will often use footnotes to comment on the primary work of somebody else. My copy of Augustine’s Confessions has footnotes listing every time Augustine quotes a Bible verse – it shows you where the quote is from, so you can go look it up for yourself. The editor obviously decided against in-text citations, where you add the citation in brackets at the end of a sentence (eg Harper 1960, 74). They could have done that, but they decided to put the notes at the bottom. They didn’t want to interrupt the original flow, and probably they also didn’t want to imply these references were in the original text. You can always explain that sort of interpolation in the introduction, but – ah, who reads those.

In all of these cases, there are a bunch of different organising tools we use to structure and deliver information. It’s not rocket science – it’s the sort of thing that we use all the time without really thinking about it. Even something as simple as the two sets of brackets in my first paragraph above – they section off their respective comments as not part of the main thrust of the argument. Those comments are asides, extra details that still add something but that are sort of secondary considerations. That’s their place in the hierarchy. If we feel someone’s overusing brackets (I think we were roasting someone about it the other week), really we’re saying that the hierarchy of information is disrupted. If there’s too many asides, too many secondary arguments, the primary point gets lost.

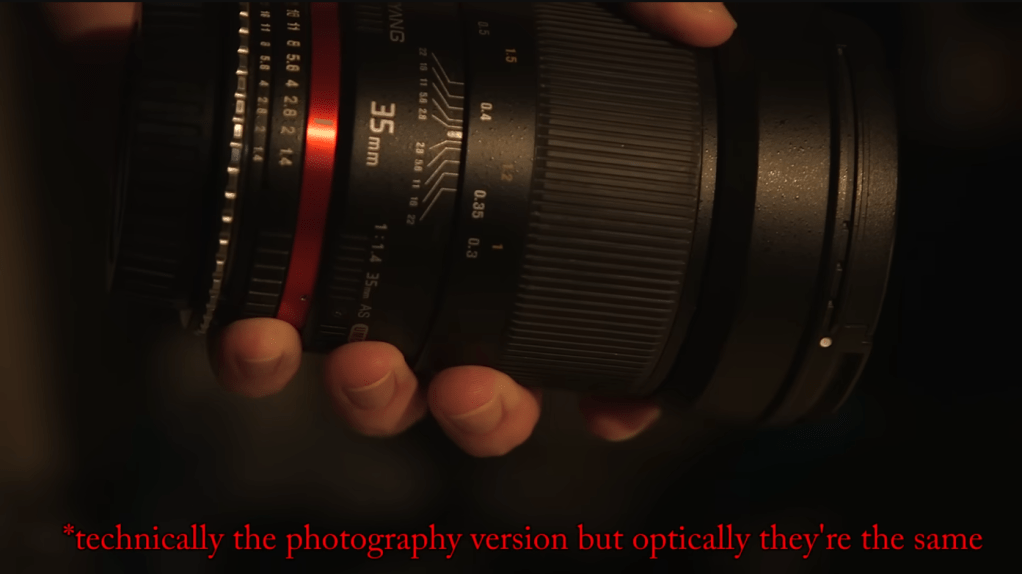

The same basic techniques of division and structure apply in video format, albeit modified for the video form. Sometimes they borrow fairly explicitly from pre-existing forms. Wes Anderson’s Asteroid City is broken into three acts, a division obviously borrowed from theatre. Youtube videos have their chapter divisions, and some videos explicitly flag those divisions in the actual video itself. They’ll tell you that you’re moving between chapters. ContraPoints has a video titled ‘Men‘ that jokingly titles each of its sections as Axiom One or Proposition Two, along with placards and cutaway background shots. There are also sometimes instances that are best understood as video footnotes. At 1:25 in hbomberguy’s 2017 video ‘Here’s Three Stories About YouTube Plagiarism‘, he talks about using a lens he saw in another video. In voiceover he describes it as “the exact same lens,” a phrasing he corrects with the asterisked text below: “*technically the photography version but optically they’re the same”. He says something verbally, and then corrects or clarifies the statement in text.

It’s a fairly common technique across a bunch of different Youtubers, and it always goes in the same direction. It’s never voice correcting text – it’s always text correcting or modifying voice. Dan Olson from Folding Ideas does it in his 2021 video ‘The Nostalgia Critic and The Wall‘: he talks about Corey Taylor, “the frontman for nu-metal band Slipknot”, and then in a quick text box on screen says “I want nothing more in the world than for people to argue at great length in the comments over the definition of ‘nu-metal’, the proper spelling, if Slipknot counts, and if that’s an insult or not.” Todd in the Shadows does it too in his recent video about Kendrick Lamar’s ‘Not Like Us‘. He explains that he doesn’t understand a particular line in the song, and then has a lengthy footnote saying:

“*When I previewed this video on Patreon, I got a lot of comments offering many different explanations of this line to me, none of which I found very convincing. You can also leave a comment explaining why this is brilliant wordplay that I’m clearly too stupid to get, but I’d prefer that you didn’t.”

Notice he includes again the asterisk, a hangover from books, where a footnote is indicated through an asterisk or star. It cues us up to recognise how this text is being deployed in relation to the rest of the video. It’s secondary, a sub-thought, something that doesn’t make it into the limelight. And none of this is earth-shattering stuff, right, but it does give us some interesting insights into the nature or culture of Youtube videos. We’ve all seen lectures or presentations where someone puts slides up on the screen and then just reads them out. The text on the screen, in that scenario, is the dominant mode, and the spoken word seems secondary. You want to just get a copy of the slides and run, because what they’re saying doesn’t really add any value to what’s written down. In these Youtube examples, voice is supreme. The natural flow of each person’s speech, often almost conversational, has its own demanding rhythm. It needs a certain pace. They are, in the first instance, talking. The textual asides are often only shown for brief moments – they flash up and then disappear. For the most part, they require you to step out of the flow of the video – to pause, go back, stop the video so you can read what’s being said. The way you interact with them takes you out of the flow of the video, out of the flow of the primary mode. Where a footnote in a book displaces you spatially, pushing you down to the bottom of the page, a footnote in a Youtube video displaces you in time. It takes you out of the video playback and makes you pause to read in full. That tells you something about the hierarchy of information in Youtube videos. It’s voice and time over text and space. As when we’ve talked previously about Youtube videos (Video Essays, Video Games), these terms aren’t bulletproof, but they start us down the road to thinking about how the medium works.

[…] that are meant to be dramatic and cool, but they’re not. We’ve talked before about Jim Butcher‘s knack for the strong cliffhanger or dramatic moment to close out his […]

LikeLike