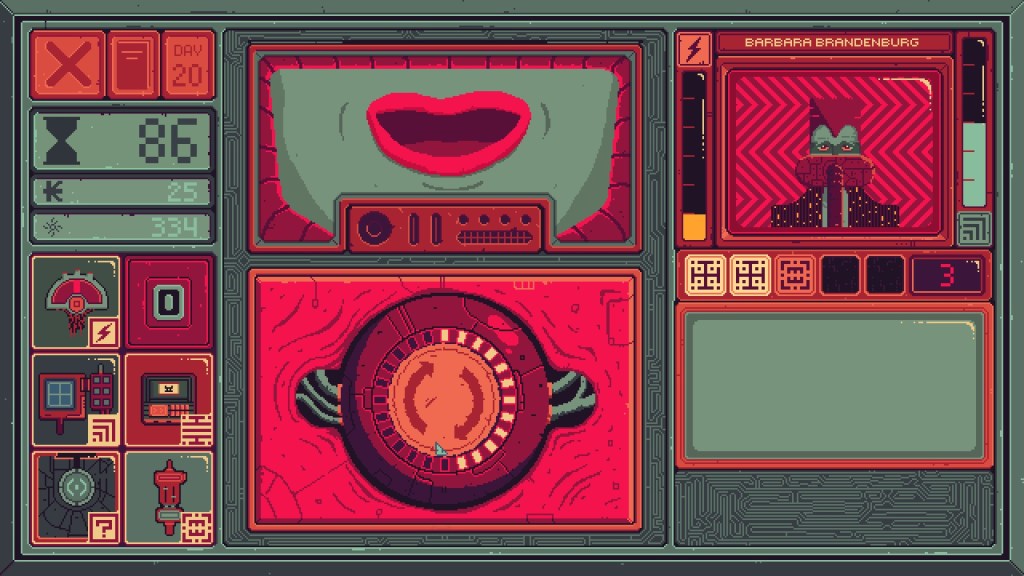

Alright, it’s time for our annual episode of having complicated feelings over a game that deals with authoritarianism and mental illness. Mind Scanners is a 2021 game developed by the Danish studio The Outer Zone and published by Brave at Night, the UK studio behind Yes, Your Grace. It is a dystopian bureaucracy game in the style of Papers, Please or Orwell, except this time you go round scanning people’s brains and curing their mental illnesses. It has all the general markers of the genre: there is a resistance group and government surveillance, and you can choose whether to side with the rebels and bring down the government or reinforce the status quo. The visual style directly evokes Papers, Please, with that sort of 8-bit faded pixel aesthetic, and even more explicitly in how characters are depicted. Like Papers, Please, Mind Scanners exaggerates facial features and uses non-naturalistic colours for skin tones. It’s a grubby version of Fauvism – it takes that Derain or Matisse idea of deliberately using the ‘wrong colours’ (so to speak) to draw attention to different aspects of the world. You make a tree trunk blue instead of brown to show how the shadow falls in the setting sun – all that sort of thing. That’s what they’re doing by painting Raymond Brittle (below) in that pink-red. Papers, Please does the same thing with its blue or purple characters. It makes the world look bent out of shape, but also tells you something new about it.

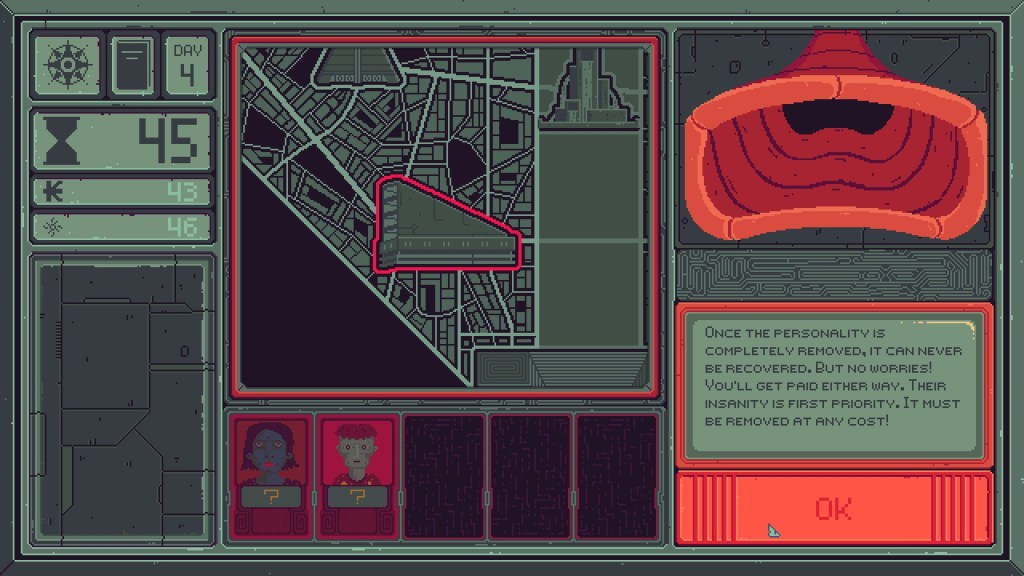

That sense of being disrupted or bent out of shape fits with the core gameplay loop of curing mental illness. You play a Mind Scanner, a member of the city administration (the ‘Structure’) tasked with diagnosing and treating so-called “anomalous citizens”. You’re given a list of subjects each day, and you have to fly around the city treating them through a series of minigames that change depending on each person’s particular disorder. The gameplay challenge is to balance your time against safe, successful cures. Like Papers, Please, you’re charged a daily fee for living costs. You get paid by curing people, which you can do with varying levels of care. If you’re short on cash, you can brutalise someone and get a quick payout. You essentially rip their personality out of their body, leaving behind a shambling shell. Thus the razor’s edge: you’re hounded by the financial demands of an uncaring system, working to treat patients with care without sacrificing your own livelihood. If you’re slow, you’ll get evicted. If you make mistakes, you’ll stress the patient and they’ll stop working with you. If you don’t take steps to protect their personality, they’ll end up functionally lobotomised. Also, the revolution wants your help to overthrow the government.

As noted, the player lives under the Structure, an authoritarian state. The symbolism isn’t overt in the visual design of the city – it’s more in textual details and in the heavy reliance on Papers, Please, itself set in a fictional Soviet state. The local currency is the kapok, obviously borrowing from the Russian kopek. There’s also that same dynamic of intensive state control over the individual, borrowed from Papers, Please but focused here through the concepts of sanity and deviance. The Structure’s rallying cry is ‘For normalcy and the mind!’ It’s clear that normalcy, so-called, really just means submission to the state. Personality destruction counts as a cure. You can help people and make them more well-adjusted, or you can lobotomise them – and the state considers both options to be equivalent. Obedience in Mind Scanners is considered the same as sanity.

This framing obviously raises a whole bunch of questions about what mental health even is. By associating mental health with social conformity, Mind Scanners draws out the double meaning of ‘disorder’. You can be both disordered and disorderly – it refers to both a mental condition and a social disruption. It exists on both levels. Mind Scanners highlights the overlap between mental order and social order, where compliance or obedience serve as markers of mental stability. You’re not normal unless you’re doing what the government wants. We’ve talked about this problem in the past with regard to autism – how the diagnostic criteria of ordered and disordered, normal and abnormal, are so heavily dependent on cultural context. Who decides what’s normal? Who decides what’s ordered? In Mind Scanners, it’s an authoritarian government. If someone doesn’t quite fit under the Structure’s regime, they are treated for insanity – treated aggressively until they get back in line. If they end up lobotomised, it’s not the worst outcome. “Their insanity is first priority,” you are told. “It must be removed at any cost!” Mind Scanners warns us that a medical framework can be used as a tool of social control. Sane and insane are social, political categories as well as medical concepts. They can be weaponised by the state.

The interesting thing here is that Mind Scanners, having said all that, doesn’t abandon the idea of mental health altogether. Some people that you encounter in this game do seem genuinely distressed, really struggling with actual problems. You don’t exactly cure someone’s bipolar disorder, but it’s pretty close. Britta Braun, for instance, thinks she’s invisible. If you talk to her, you learn that she has self-esteem issues. “Problems of self-worth has [sic] led Britta to actualise the idea that she is invisible to other people.” You can help her with that. You can treat her and raise her confidence. She can go away a better, more well-adjusted person, which is a wild thing to say in the context of an authoritarian dystopia, but here we are. Other characters aren’t insane, per se, but they suck. Don D’Alonzo is a power-mad security guard. Logan Guislain is a successful surgeon who’s violent at home. You can improve these people. You can make them kinder, gentler, more empathetic. You can fix them. It all fits together in a troubling sort of way. Mental health is a trick to make you submit to the government, but you can also use it to help people who are suffering. Also, because you have total power over the population, if you meet an asshole you can declare him insane, and forcibly impose treatments on him until he’s a more rounded human being. This I think ultimately seems like a gap in Mind Scanners: it critiques the institutions of mental health as a potential tool of a coercive social structure, except when you do it. You can just help people. You can help people, and improve people, and overthrow the government, and that’s all fine. The tools are dangerous, but not in your hands. Mind Scanners has this really nuanced critique of mental health and state power, which it ultimately gives over in favour of a classic video game power fantasy. It’s the same problem we saw with Beholder. It’s a critique of power that doesn’t think too hard about the player. It’s a shame.

[…] Insanity and Government in Mind Scanners(deathisawhale.com, James Tregonning) […]

LikeLike

[…] see this slightly glib approach to regime change in plenty of other titles, like Papers, Please or Mind Scanners, which we talked about recently. In both of those, there’s a slightly oversimplified […]

LikeLike