The John Wick films have an interesting internal relationship with each other. They showcase a bunch of interesting things about how sequels work – about how films or stories more broadly connect with each other, how they operate as units both on their own and in concert. If we wanted, we could probably draw up a rough taxonomy based around these films.

As a starting point, let’s set our two poles of the spectrum as the trilogy and the two-part film. The key distinction between them is not the number of films – it’s not about two vs three – but the structural difference between a string of distinct-but-connected titles and a pair of films that are really better thought of as two halves of a single story. Take for example the original Star Wars trilogy. Episode IV, A New Hope, is obviously a stand-alone first film. It’s relatively self-contained, resolving all of its key narrative beats by the closing scene. It opens with Darth Vader pursuing Princess Leia and the Death Star plans, and it ends with Luke using those plans to blow up the Death Star. A threat is introduced and then resolved. Episode V, The Empire Strikes Back, is by contrast a bit of a floating movie. It’s not particularly close to the episodes on either side – it’s probably technically closer to the latter film, but only in that it brings characters from the context of A New Hope towards the setting of Return of the Jedi. Luke trains with Yoda, he learns a secret about Darth Vader, and the Empire chases the Rebellion about the place. It’s clearly missing that sense of self-containment that we find with A New Hope. It’s preparatory. It’s not bad – it obviously has its own narrative integrity and structure – but in terms of its place in the trilogy, it’s probably slightly more about preparing the characters for Return of the Jedi. It’s transitional. It reshapes the universe of the first film to fit into the context of a trilogy. I think we see that with a bunch of middle films in trilogies – Catching Fire, for instance, in the Hunger Games trilogy, is about moving Katniss from the independent first film into the context of the overarching civil war in Mockingjay. (Mockingjay is of course spread across two films, making this set technically a quadrilogy, but structurally it still has that three-part process – Hunger Games, Catching Fire, Mockingjay.) Catching Fire gets Katniss out of the context of The Hunger Games and ready for Mockingjay. The Empire Strikes Back functions in a similar way. Both are second films looking towards the third.

At the other end of the spectrum is the two-part film. As noted, Mockingjay in the Hunger Games trilogy is a film in two parts, released in 2014 and 2015. There are plenty of other examples – Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows parts 1 and 2 in 2010 and 2011, Dune in 2021 and 2024, so on. These films are slightly slippery – the easy definition is to say that two-part films come with Part One and Part Two in the title. They are two-parters because they tell you they’re two-parters. That’s not particularly satisfying though – it’s a post-hoc definition, it doesn’t tell you much about the underlying logic. It doesn’t tell you why anyone would pitch something as a two-part movie rather than, say, a duology. It doesn’t bring us in. We might start instead by saying that two-part films are paired films comprising a single narrative unit. They are two halves of a whole, where each part technically has its own narrative integrity, its own arc, its own beginning and end point – but they have that integrity in the same way as chapters in a book. They have a structure, but they’re not really independent. They’re not complete without the other half. You can see already that some of the language here is a little difficult – it is sometimes hard to map a definitive break between two-part stories and trilogies. In both cases the films are connected – they feed into each other, they make sense in the context of the units as a whole. There will be trilogies where two of the films could potentially be reframed as Part One and Part Two (and when Dune: Messiah comes out, we’ll have a good example of exactly that). We end up back at our basic assertion: if we had to point to a clear distinguishing feature between the trilogy and the two-parter, it might be that two-part films are built around a single narrative unit. There might be one quest or goal set out in the first movie, and it’s not achieved or resolved until the end of the second – such that both films are oriented towards, building towards the end of the second movie. That’s – again – not a bulletproof definition, but it’s a starting point. For our purposes it probably helps that all three of the examples above are adapted from books – so there actually is a single narrative unit out in the world that we can point to as holding the underlying unity of the two parts.

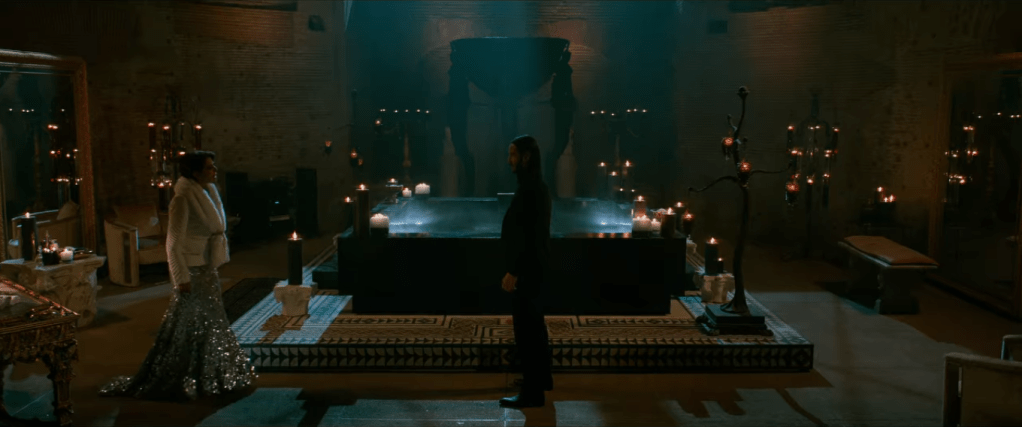

Within that framing, the John Wick films serve as an interesting case study. There are four John Wick films over the last ten years: John Wick (2014), John Wick: Chapter 2 (2017), John Wick: Chapter Three – Parabellum (2019), and John Wick: Chapter 4 (2023). Starring Keanu Reeves as the titular Wick, the films are essentially nonstop action movies, where the narrative serves primarily as a vehicle for fights. They’re directed by Chad Stahelski, a stuntman and stunt coordinator – so they’re very focused on interesting fights, if I can use that language. They like exploring combat on-screen with a bit more versatility and depth than your standard Hollywood fare – showing stuff that you don’t really see in other places. The emblematic example is in John Wick 2, where Keanu murders a hitman with a pencil. You’d be unsurprised to learn the plot is thin – just enough to string together otherwise unrelated combat sequences. In the first film, John Wick is a retired hitman seeking revenge for his murdered dog. That’s it. It’s less a narrative and more a framing device, serving mostly to create room for technical inventiveness and choreography. At times, you could just about swap the order of some of the fights without interrupting the overall logic of the film. In John Wick 3, for instance, the first twenty-five minutes feature fights in an antiques store, in a stable, and in the New York Public Library. The fights follow on from each other, as each conflict ends with Keanu getting spotted by the next group of assassins, but there’s no inherent logic as to their progression – it would be trivial to rearrange the order of scenes. On the whole, the franchise is a perfect example of filmmaking in the Gen Z era. Where older films might put more effort into the framing narrative, to justify and sort of legitimise the violence, the John Wick films rip away the façade. They disregard the pretense, the social niceties. They are here for gun fu and fight scenes. It takes Gladiator an hour to get into the arena. John Wick 3 features death by library book in the first nine minutes.

We’re going to pass over the first film, then, which sits comfortably as an original stand-alone title, similar to A New Hope, and we’ll skip the fourth, which serves as a bloated extension to John Wick 3. Both first and fourth films fit relatively cleanly into a trilogy model – which, to repeat, is not specifically about the number of films, but instead about a stringing together of titles. They are sequential titles, if that term fits better. The interesting part happens between John Wick 2 and 3. Those films revolve around one action at the end of John Wick 2. They aren’t parts one and two, but they are joined together and about each other. They are magnet films, so to speak – independent, discrete objects that are deeply concerned with their opposite title. John Wick 2 sees John Wick forced to kill on behalf of a crime lord, Santino D’Antonio, who wants his sister (Gianna D’Antonio) dead. Wick owes Santino a favour, so Santino makes Wick kill her. After a movie’s worth of double crosses and triple crosses, Keanu walks up to Santino in the grounds of the Continental – a hitman hotel where you’re not allowed to kill anyone – and shoots him in the head. Thus the events of John Wick 3: Wick, excommunicated from the hitman brotherhood, flees for his life as the city’s assassins come after him to collect an enormous bounty. John Wick 2 is about John Wick 3, which is normal. It leads into its sequel, in the same way that Empire Strikes Back leads into Return of the Jedi. What’s interesting is how much John Wick 3 looks backwards. It’s very much about John Wick 2. It’s the fallout.

Again, this language is slippery, and the distinction can be hard to grasp. Sequels are always based on the events of the previous film, and the events of the previous film lead towards the sequel. That’s not unique or interesting – it’s just chronology. What’s interesting with John Wick is that the key event, for both films, is located at the end of the second title. Santino’s death is the centerpiece, the heart of both stories. Everything flows towards and then away from that moment. It is the vortex at the center of both parts. In other trilogies, the second film can serve as a sort of prologue, or a transitional narrative getting things in place for the third film. The second film points towards the third, and the third is centered within itself, with its own narrative beats and climax. The center of John Wick 3 is the end of John Wick 2. It flows in a way backwards. It is only what comes after. As a point of comparison, the third season of Hannibal functions in much the same way. Season Two ends with a bloodbath, with Hannibal gutting Will Graham, murdering their surrogate daughter Abigail, nearly murdering Jack Crawford, the head of Behavioural Sciences at the FBI, and then their friend and colleague Alanna Bloom gets pushed out a window. The first half of the following season sits in the wounded glow of that event. People spend a lot of time sitting around, thinking about that experience. They reflect on the people they lost. Jack Crawford catches up to Hannibal and has a deeply cathartic time throwing him around a museum exhibit. The second half of Season Three has a time jump, focusing on the Tooth Fairy killer from Red Dragon, but even then it sits in reference to the end of Season Two. It has this dull, anesthetized energy. It’s muted. Nobody has recovered. They’re trapped in the aftereffects of that traumatic scene. John Wick is the same. The focal point for both the second and third movies is the end of the second one, where Santino gets shot. Everything is built around that point.

And you can see the difficulty in framing this idea. John Wick 2 and 3 are not just parts one and two of a single story. They are not like the two parts of Deathly Hallows, where Harry finds some Horcruxes and then he finds some more. They’re sequential films, part of a sequence of relatively independent stories that are strung together to form an overarching narrative. But they both center themselves around the end of the second movie. The clearest example of the difference, actually, is in the bridge between John Wick 3 and 4. The third movie ends with another cliffhanger – with Keanu betrayed by Winston, his closest friend and ally. John Wick 4 could build itself around that moment, but it doesn’t. Wick and Winston reconcile by the end of the first act, and John Wick 4 moves on to be about itself. It centers in and builds around its own story. It borrows from the events of earlier movies, but it isn’t oriented towards them. The first and fourth movies sit relatively self-contained, at least in terms of their orientation and arc. The second and third movies pull towards each other. They lead towards a shared center at the end of the second movie. It’s a weird, fascinating little structure – not trilogy, not two-parter, but clearly built around and oriented towards a key moment sitting between the two films.