The Australian Defence Force has had a bad time lately. The Brereton Report, an investigation into allegations of war crimes in Afghanistan, found “credible” evidence of unlawful killings. Ben Roberts-Smith, recipient of the Victoria Cross and known as Australia’s most decorated soldier, brought defamation charges against a series of newspapers for reporting on alleged war crimes: Roberts-Smith ultimately lost the lawsuit, with the judge accepting the defence of truth and finding that, on the balance of probabilities, Roberts-Smith murdered unarmed civilians. More recently, commanding officers in Afghanistan have been stripped of their medals and awards, a Royal Commission into veteran suicide has found combat veterans taking their lives at twice the national average (vol 1, p14), and the ADF are failing to make their recruitment quotas. It’s all pretty dire. Fortunately, they’ve got new recruitment ads aimed at zoomers.

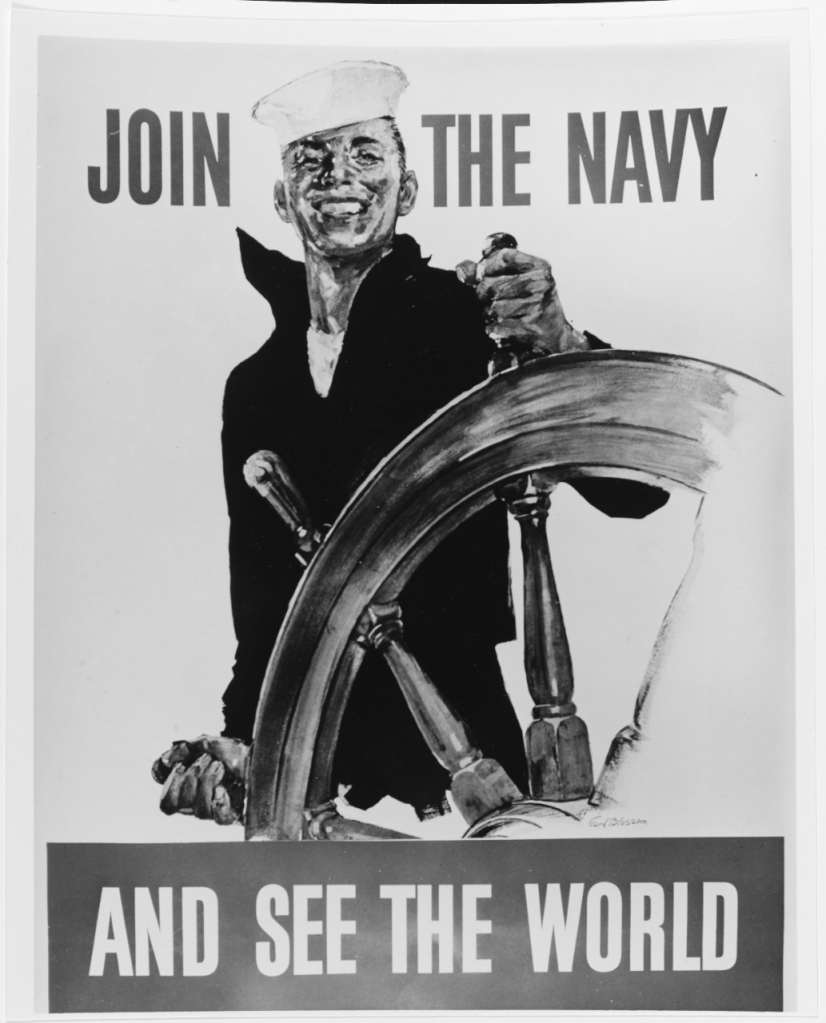

Launched in July 2024, the ‘Unlike Any Other Job’ campaign aims to raise awareness of the range of ADF roles available across the armed forces – navy, army, and air force. It’s bad. I’ve seen it run a couple times in the cinema now (including before Wicked, which seems like an odd target demographic), and it gets worse with every watch. The pitch broadly is about the possible life experiences instead of the role itself – a rehashing of ‘travel the world, meet new people – and shoot them’. It’s appealing to those inward-focused, personal values like fulfilment or growth, instead of nationalist or communal values like ‘protect your country’ or ‘serve the homeland’. In a Conversation article back in June, a couple academics paid by the Department of Defence wrote that “Zoomers want a calling and not just a career”. This ad campaign more or less responds to that finding. That’s not a new thing in itself – military recruitment has always articulated itself in terms of the culture and values of its time. In the UK during the First World War, you had posters with titles like ‘Daddy, what did YOU do in the Great War?’, with this dad looking real guilty for not going to the trenches. Australia had similar efforts – ‘Which picture would your father like to show to his friends?’, with a soldier in uniform set against some louche in a deckchair with his tennis racket. There are appeals to camaraderie, with soldiers about to be bayonetted by the Germans (‘Quick!’), appeals to masculinity (‘Be a man and do it’), and this awkward but fascinating recruitment poster from Queensland, which was aimed at women instead of men. “Remember how women and children of France and Belgium were treated,” it reads. “Do you realise that your treatment would be worse? Send a man today to fight for you.”

In each instance, the posters are designed to appeal to the social norms of the day. Real men fight in wars. Women need men to protect them. Better go to war, or your dad will be embarrassed in front of his friends. All the greatest hits of 1918. The zoomer ad is then in turn focused on the values of people today – on a meaningful career, on doing a job that’s more important than just some 9 to 5. There’s a transcript of the ad below, and then we’ll get into the guts of it.

“If your workday starts early, start the day right.

Do more than send emails: send critical intelligence.

When you travel for work, travel undetected.

If you’re good at building networks, get even better at finding them.

And if you work late, work to defend what matters.

If you use your hands, keep this moving, this firing, this flying.

Visit places you can’t find with a hashtag.

Because this is more than just a job.

This is an ADF career.

Make your impact.”

In the first instance, we should acknowledge that some of these sentences don’t really make sense. Nobody is looking to travel to work undetected. That’s not – I don’t know what that’s supposed to mean. That’s not a high priority for anyone. The clip juxtaposes the ‘working late’ line against the visuals of a night raid on some two-story apartment block, which is how it connects the ideas of working late and defending what matters, but that’s also a bit of a stretch. Other language is fairly straightforward marketing pap. The contrast between critical intelligence and boring emails is an authenticity play, echoing Steve Jobs’ famous line to John Sculley, then-vice president of PepsiCo: “Do you really want to sell sugar water, or do you want to come with me and change the world?” As Philipp Schonthaler notes in Portrait of the Manager as a Young Artist, the Jobs exchange is a bit of an emperor’s new clothes situation. It’s the gap between product and lifestyle, between the narrative or brand of Pepsi and the dull reality of carbonated soda. The point, Schonthaler says, is that it’s all just marketing. Like Sculley, Steve Jobs was also telling stories about his product. He was telling stories about the brand and identity of Apple – it’s world-changing, it’s epochal, it’s more than just a retail computer company with some expensive products. In that anecdote, Jobs exposes the artificiality of the Pepsi narrative to bolster his own company’s authenticity. Do you want to sell sugar water, or do you want to change the world? That’s fake, this is real. The same rhetorical flourish is at play in this ad: do you want to send emails, or do you want to share critical intelligence? In reality, they probably send intelligence via email anyway – the point is the framing. They’re gesturing towards authenticity and purpose – claiming it for themselves in opposition to something else. Emails are boring, intelligence has a point. Emails are fake, intelligence is important. It’s propaganda – it’s marketing. The ADF points to the lie at the heart of the corporate workplace to bolster their own authenticity.

Other lines in the ad have a pretty similar function, albeit with varying results. Consider the hashtag quip: “Visit places you can’t find with a hashtag.” It’s set in opposition to the performance of social media and influencers, set against curating identity online. This isn’t just a trip to Bali, they’re saying. You can get beyond the hashtags, beyond that level of social performance and into the real. The actual line itself is again not totally coherent (who finds places with a hashtag? what does that even mean?), but that’s the underlying rhetoric. It’s probably less successful than the emails / intelligence line, partly because the idea of ‘travel the world, join the navy’ is already so ingrained in our culture. It’s a cliche, to the point where it’s better known as parody – travel the world, meet interesting people and shoot them. I think also there’s a more subtle dissonance here between travel as leisure activity and travel for work. The line is pitched to you like it’s part of a tourism campaign – as if it’s targeting holiday-makers – but the ad as a whole exists in the context of employment. It’s all about starting your work day and travelling for work – travelling undetected, of course – so this sort of holiday rhetoric doesn’t really land. They’re confusing meaningful work with meaningful play. Wanting a meaningful job doesn’t mean wanting to “visit places you can’t find with a hashtag.” Those are not the values zoomers care about.

Despite that wobble with the hashtag, the ad as a whole tries to position the military in the context of beauty and awe. The hashtag line is accompanied by the visual of a bunch of photogenic young people splashing about in the ocean. The ad opens with this lingering view of blue ocean under the rising yellow sun, and then a fighter jet flies through the frame – so it’s product placement, sure, but with a focus on this gorgeous environment. The light of the rising sun is low, playing off the front of the waves while leaving their rear in shadow, and it’s gradiated down the screen from this sort of early orange light through to dark blue sea. There’s this sense of awe and almost sanctity. It’s paired with plenty of classic military moments – tanks and missiles and so on, and the soldiers raiding the apartment block – but there’s also this strong focus on beauty and the glory of visual spectacle. Everything seems to happen at sunrise or sunset. The final shot has soldiers in shorts and t-shirts jogging along a sandy beach, with the sun gliding down towards hills in the background, and a glorious gold and peach sky. It’s not just submarines and tanks, and high-tech mission surveillance – it’s gorgeous.

And that’s probably where the gaps become apparent. This airbrushed view of the military sits against everything we know about war. It sits in the face of the Brereton Report, in the face of the royal commission. We know. We knew when Vietnam was going on, we knew with the First World War – Robert Graves published Over the Brazier as early as 1916, with poems like ‘Limbo’ giving a realistic account of the trenches: “After a week spent under raining skies,/ In horror, mud and sleeplessness, a week/ Of bursting shells, of blood and hideous cries”. You can’t airbrush this stuff. The ad tries to make beautiful something really ugly. They trot out this authenticity gambit, playing up how office jobs are fake and boring – but their proposed solution to the fakeness of office jobs is going into a war zone. You can’t slip this stuff past people – especially not zoomers. In the 90s you could play funny army recruitment ads with people whistling the 1812 Overture. That doesn’t work any more. And you can’t just gloss it up, either. They’re trying to grab this target audience by making the military seem deep and meaningful – more substantial than an office job. But you can’t pitch depth in a shallow way. If your ad plays up the value of thoughtful, meaningful consideration, it’s going to receive thoughtful response – and in the face of the facts, most of the time that response is going to be negative.