I have mixed feelings about Borderlands 4. Apparently I’m not the only one – at time of writing (26 Sept 2025), the game has 63% positive reviews on Steam, giving it an overall rating of ‘Mixed’. Borderlands 4 released not quite four weeks ago, on September 12. In the early period after launch there have been some issues with the graphics, particularly for players on PC, which is not necessarily unprecedented – it’s reasonably common for high-end games today to release with bugs or other performance issues which are smoothed out over time. I encountered one bug that soft-locked the entire game. I closed the game halfway through Zadra’s monologue in her cave, and when I reopened it, there was no flag to restart her monologue. She couldn’t finish speaking, and so there was no trigger to start the game’s next quest. I couldn’t continue. That’s a pretty ruinous soft-lock, but it’s also fairly normal for right after launch. There was an informal fix to jump-start the flag (start a second campaign, and then load back into the first one), and more recent patches have solved the issue altogether. I’m not mad about it. Other people’s problems have been more serious. For some people, the game just does not work. It’s stuttering, it’s slow, it’s crashing out – and it’s not just an issue of people with older systems. It’s actually two groups of people with overlapping complaints. One group are just straight up-and-down not able to play the game. It’s just not functional, at any level. Another group of people (with very expensive graphics cards) seem to be mad that they can’t play the game on its highest settings. It runs, but they can’t boot it to max without encountering the same sorts of issues – stuttering, slow, crashing. All of the symptoms are the same for two different reasons, and so the two groups coalesce around the critique that the game isn’t ‘optimised’.

I want to try and tease the two groups apart here, at least a little. The people who can’t play the game at all are obviously in a bad situation. They’ve spent a lot of money on a brand new expensive video game, and they’re upset that they can’t play it. The people with the expensive graphics cards can play it (or at least some of them can), but they’re mad that they can’t play it at top settings. The attitude is almost – hey, I put a lot of money into my computer, I bought top of the line, I expect to be able to play everything at max graphics, and if I can’t, your game sucks. It’s not – the key term – optimised. Neither group is wrong, per se, but I have less sympathy for the second group than the first. In some ways I didn’t really understand that the second group existed – I just can’t imagine getting mad about having to turn my graphics down. That’s a very foreign way of thinking about video games – which is ultimately a reflection on me, rather than them. I’m a very boring, non-technical player. I tend to buy a mid-range computer off the shelf every ten years or so – honestly I’m sort of surprised by the idea of hating a game for its technical performance. It’s a problem if you can’t play it at all, but getting mad for having to turn your specs down – that’s a very unfamiliar way of thinking.

This whole graphics conversation raises a question around the basic idea of reviewing a game. We can talk forever about character and plot, dialogue, pacing, art direction, thematic unity, but next door there’s some guy howling about how he had to turn the graphics down from Badass to Very High. People care about such different things – it almost makes the idea of a review seem incoherent. There’s no unity. 6/10, characters seem underdeveloped; 6/10, can’t play in bath. These feelings lap over into my thoughts on the game itself. In terms of gameplay, it’s a runaway success. Borderlands 3 introduced certain maneuverability features previously absent from the series, and Borderlands 4 has improved on them again, introducing a grappling hook and a glide function. It’s sort of shocking how much depth these simple couple features add to the gunplay. The increased range of movement gives a new vocabulary to combat, where certain types of attack need to be dodged in certain ways. They’re not complex or unusual movements for video games as a whole, but they’re new to the Borderlands series. The gap in gameplay between Borderlands 4 and, say, Borderlands 2 is astronomical. You’ve always had these explosive barrels scattered around the landscape: now you can use the grappling hook to pick them up and hurl them. You’ve previously had to decide if you’d waste a weapons slot on a rocket launcher, which you’d keep in reserve for boss fights (because the ammo is fairly rare); now rocket launchers share a slot with grenades: as so-called ‘ordnance’, they both operate on a cooldown timer rather than needing ammunition. There’s so much verticality and movement to the combat, where you bounce around like this rabid electrolyzed creature, spinning and jumping and changing targets – the rhythm of gameplay has tilted towards this new, manic style, almost closer to DOOM or Quake, and it’s very much to the game’s advantage. There are so many strong quality of life improvements. You can mark loot as junk when you pick it up, meaning you can just sell it immediately without having to sort back through everything and figure out what’s worthwhile; you can summon a vehicle anywhere rather than hiking back to the vehicle station every time – it’s a meteoric change.

At the same time, the world-building is easily the dullest in the series. The developers took a conservative approach, clearing the board and starting over, seemingly in response to negative feedback around Borderlands 3 – which is really a problem with roots in earlier games. The Borderlands series has long been dominated by the figure of Handsome Jack, the villain of Borderlands 2. A stand-out mix of charisma, sarcasm and violence, Jack spends his time trying to kill the players, declaring that he’s actually the game’s hero. He’s in the same realm as Vaas from Far Cry 3 – lightning in a bottle capturing something inherent about the series. Borderlands 3 tried to tap that vein again with the villainous Calypso Twins. The pitch is that they’re streamers who start a cult, which is, as a pitch, pretty funny, again capturing that combination of megalomania and aspiring to be the hero. There are considered, crafted themes of family, summed up by minor antagonist Lady Aurelia (“Troy, dear. You’ll figure this out eventually – family is just another word for war”), and a cast of thousands, with almost all of the playable characters from previous games making an appearance to egg on the new generation. There were wobbles in the story’s execution (not an unfamiliar experience for Borderlands), but the fans complained, and Borderlands 4 has pulled everything back with a soft reset.

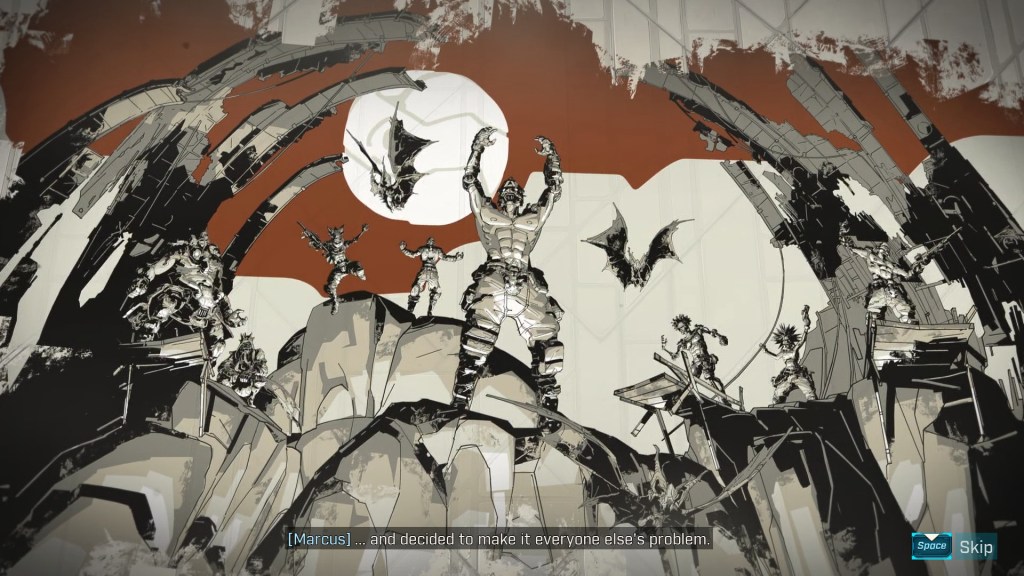

Stepping away from the galaxy-spanning quests of 3, Borderlands 4 focuses on one planet off in the shadows. There are a couple of recurring characters from earlier games, but almost none of the series staples (Torgue, Tiny Tina, Ellie, Tannis, Hammerlock), and very few from the ensemble cast of Borderlands 3. There’s a villain, but they’re more demure: where the Calypso Twins would drop in across different cutscenes, the fourth game’s villain, the Timekeeper, spends most of his time in the background. Tonally, where the Calypso Twins (and Handsome Jack) were chaotic and silly, the Timekeeper is staid and boring. It’s more serious, more po-faced – honestly just worse. Borderlands has always been a silly, rambling series. They took a big swing with the Calypso Twins, and it didn’t pay off, and they’ve retreated into an awkward, poorly-fitted solemnity. They’ve pared back the characters, pared back the overarching story, and focused on moment-to-moment gunplay, with the silliness restricted to incidental sidequests. There’s a void where the antagonist should be. They’re still living in the shadow of Handsome Jack.

Really, the game has had a shift in design principle, moving closer to The Division or other open-world looter-shooters. The story is technically present, but mostly in the background – the game revolves around a post-launch content roster designed to keep people playing over time (raid bosses, weekly quests, DLC). It’s less of a story and more of a money machine. It’s less a narrative and more a perpetual play-space, with most of my reasons for play – the characters, the world, the stupid comedy – cut back to the bone. And I’m troubled by this conclusion, right. I want to be open to whatever the game is. I want to try and take it at its merits, treat it as its own game and not just get mad because it’s different to what’s come before. There’s a whole mission early in Borderlands 4 where you help Claptrap move on with his life after crashing on this game’s new world. Claptrap, in this mission, embodies the person unwilling to evolve: “WHAT!? But dwelling forever in the faded vestiges of a lost and unreachable past is the BEST way to live!” You go looking for his personal possessions, hunting through the wreck of a spaceship called (unsubtly) the Nostalgia, and when you find his stuff, you put it on a boat and blow it up. Time to move on? I don’t know.

Borderlands 4 is a different sort of game. It’s not bad, but it’s for people who play Destiny. It’s for people who want a game with a very long tail, something that keeps them coming back, with weekly challenges or dungeons or whatever else. It’s a game with major improvements, albeit improvements that sometimes introduce problems of their own. For instance, in response to complaints of constant load screens and load times in Borderlands 3, Borderlands 4 has moved to an open-world map, which technically solves the problem, but which also feels strangely empty and repetitive, stretched across three or four simple, homogenous regions (green pastures, dusty desert, cold mountain, grubby city). There’s nothing as eerie as the swampland of Eden-6. There’s nothing as comparably inventive as Captain Traunt howling at the monks while he burns down a monastery, or Mouthpiece’s dance battle with his wub-wub shield and exploding speakers. The gameplay shines, but the characters, the world, the stupid muck-about – it’s largely dropped away. I don’t think the series can ever make everyone happy. I don’t think it should try – arguably the attempt is at the heart of its problems. In a way it almost feels like that problem also functions as a defence: I want to say the game is bad, but I keep hesitating, keep pulling back to the idea that maybe it’s just not for me.

[…] there’s no separation between the game, strictly conceived, and the world of the fiction. In Borderlands, you control a character, and other characters will move markers through a virtual environment, and […]

LikeLike