Still Wakes the Deep is a 2024 Lovecraftian horror game from The Chinese Room, the storytelling masterminds behind Dear Esther and Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture. In concept it’s a fairly straight-laced cosmic horror. Cameron McLeary is an electrician working on an oil rig off the coast of Scotland. The underwater drill hits something, and the station is swiftly taken over by an inconceivable monster from beyond. It’s weird, it’s spacey, people melt into flesh piles or octopus monsters that sucker their way around the rig – standard Lovecraft-style cosmic horror. It’s maybe five hours long. Because it’s The Chinese Room, the focus is on a closely realised environment with a high level of fidelity to a specific real-world place. Their earlier title, Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture (2015), is closely modelled on Shropshire in the West Midlands. Still Wakes the Deep is a study of the oil rig, but also of Scots culture and dialect. The subtitles, for instance, often don’t line up with exactly what’s being said. They are translations as well as captions. They’re not even translating particularly complicated terms, in honesty – “fucked from the off” is captioned as “fucked from the start” and “before his nibs blows a gasket” is captioned as “before his lordship blows a fuse” – but the point is that the game is working through this very close portrayal of Scots dialect. And it’s been very positively received, with much of the media attention around the game praising the accuracy of its accents. Personally, I’m more interested in the water.

The basic structure of a Lovecraftian story sees a rational or logical mindset cast adrift in the face of monsters from the void. The original tales by H.P. Lovecraft often start with a professor or a researcher, someone who fits into an Enlightenment tradition of evidence and reason. They go exploring, scratch the surface of the world, and discover some vast, monstrous creature that shatters their scientific worldview. The narrative of science, if we can use that phrase, is about the shift from magical mystical thinking (the gods did it!) into demonstrable evidence that can be tested repeatedly by any number of people. It’s about the shift from myth to fact, from not knowing anything to knowing with reasonable certainty. The Lovecraft arc takes that narrative and offers a second shift back into the mythological, as if to say – shit, we don’t know anything after all. All our tests and evidence are so much chaff before these eldritch abominations. These creatures are imagined to be so warped and perverse that the scientific model and in fact any sort of coherent thought or reason is cast down as an absurdity, a framework of meaning with no genuine foundations in reality. Lovecraftian horror, at its core, is about the unmooring of rationality. It’s about logic cast adrift.

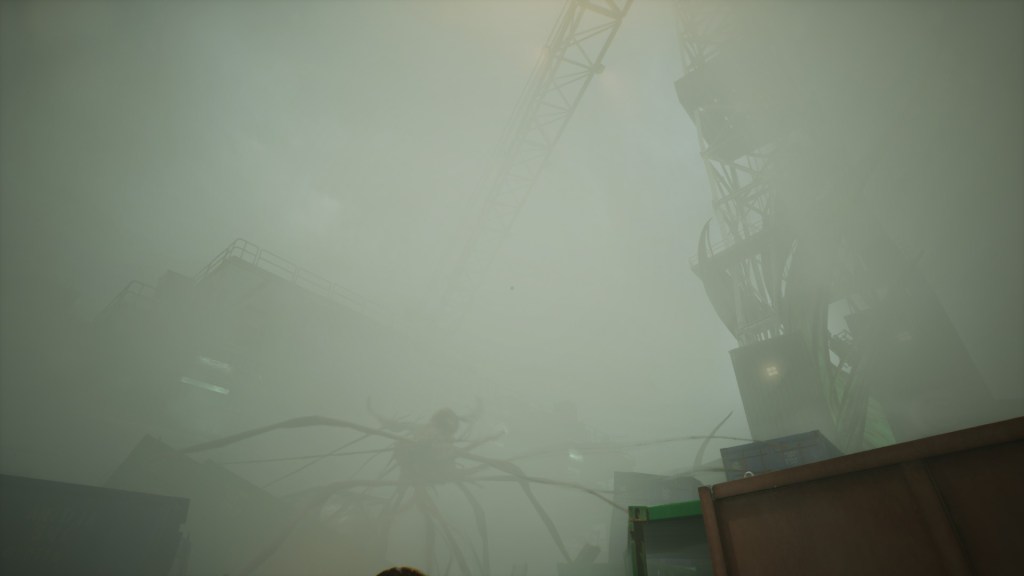

In Still Wakes the Deep, that transition is explored through the conflict between the rig and the sea. The rig is a human construct, a model for making meaning and sense of the world. It is, metaphorically, our logical or scientific worldview. It is a deeply technical construction, relying on the hierarchical stacking of evidence and experiments and all sorts of innovations. It’s not a shallow structure – it’s not a raft or a dinghy. It has complexity. And it gives form to the player’s experience. Accommodation is over here, engineering is there, the drill’s that way and the helipad is up top. The rig offers stability and shape. It’s juxtaposed against the ocean, which is shifting, unstable, free of fixed form. The ocean is portrayed as seemingly boundless – there’s no sign of nearby land, and in places not even any meaningful distinction between grey ocean and cloudy sky. They merge into one unending void. The Lovecraftian monster in Still emerges from the water, from beyond the limit of our understanding. The drill extends into the deep, and our framework is not strong enough to withstand what we find. The monster, accordingly, causes the rig to break down and collapse. As in the Lovecraftian narrative, its mere existence shakes apart the apparent stability of the scientific method. Everything on board goes through a process of deconstruction. The creature’s limbs (fins?) burst out through broken pipes. Electrical systems fuse, lifts break, crates are hurled across the decking by explosions and collapsing scaffolding. Human bodies, too, are torn apart and reconstructed – as their own eldritch beasts, disassembled and rebuilt into wet, watery things, with too many limbs or suckered tentacles, or just pulsating, bulbous lumps. There’s no natural order, no technological prowess – Still is a game about the collapse of what we know in the face of what’s beyond.

Despite this impending collapse, the surviving human characters spend all of their time making plans and trying to execute them. They continue to operate on the assumption that the world makes sense – that the situation can be resolved in a rational way. They run for the lifeboats, then the helicopter, then they try to stave off the rig’s impending explosion. They’re always trying to carry out some sort of plan. It’s neat to see the game use its own task-driven nature to illustrate its characters’ hopeless commitment to cause and effect. Their behaviour is rooted in a world that makes mechanical, logical sense, where things exist in a causal relationship. Their constant pursuit of the next task is really the heart of their tragedy: they don’t understand, they’re not equipped to understand, and they’re never really going to get it. They are too rooted in their rational ways of thinking. They don’t get that there’s no sense any more. The only things left to them are change or death – water or the grave.

The water, for its part, is very happy to make its way up the rig. Over the course of the game, areas become flooded and unmanageable – the rig descends out of order and into the anarchy of the sea. It proceeds from form to formlessness, from fixity to fluid. Certain sections require you to swim (I’ve seen people describe the game as a drowning simulator), either through oil or water. The two liquids are mostly interchangeable, in terms of the metaphor, except maybe to note the implications of discovering a Lovecraftian monster while you’re drilling for oil – that is, you know – the theme of drilling into the deep for this tarred liquid that causes the world to collapse – it’s a climate change thing, right, it’s a critique of industrialisation. We learnt a couple things and reached into the deep and suddenly the world’s falling apart. The water is that state of collapse. It is the void. It is unstructured flow, opposed to the rigid architecture of the rig. It’s dissolution. The strength of Still Wakes the Deep, really, is in how the non-place of the water is set against the deeply specific particulars of the coast of Scotland. The accents aren’t interesting for being accurate, they’re interesting for articulating what is lost. They have a thematic, structural function. The game is about how place becomes non-place. The strength of that vision hinges on the sense of place. The tragedy is in knowing the specifics of this culture and dialect, watching the closely realised record of a particular time and place, and seeing it washed away.

[…] so entirely its own game – there’s really nothing to compare it to. Games like Still Wakes the Deep are clearly part of a genre – and they’re not bad for it, but there is a sense in which […]

LikeLike