We went to a small art gallery recently, and they had an ecology exhibit – fishing nets with bits of plastic and rubbish tied up in them, that sort of thing. I felt pretty indifferent about it. It’s not the idea that leaves me cold – I’ve been writing about ecology and art for years, with games like Don’t Starve, Forager, Flotsam (out of early access, time for a revisit), and Terra Nil. This is something that I care about. Possibly it’s partly the slightly preachy nature of the stuff we saw, which seemed geared towards people who’ll come in and go ‘mm yes I agree’ – but also I think it was just missing that sense of awe. And – I know this is a me problem, right – art doesn’t necessarily have to create a sense of awe, and it’s fine and interesting to explore other emotions, but I often just feel a little flat in front of these things. I want to be shocked. I want to be swallowed by the creative vision. I want to go home and play NORCO.

NORCO is a 2022 point-and-click adventure game from Geography of Robots. In concept, it’s about a girl who comes home to Norco, Louisiana and starts looking for her brother. She explores a town riddled by poverty and the panaceas of religion and technology, while wealthy oil companies rip the gold out of the soil, flood the town, and destroy the bayou. Norco is actually a real place along the Mississippi River, in the so-called Cancer Alley: the game draws its strength from a close observation of that region’s history. If you’re not familiar, Cancer Alley is a stretch of land along the Mississippi River (between Baton Rouge and New Orleans) with a high concentration of petrochemical plants and refineries – something like 25% of all US oil production. It’s called Cancer Alley because the constant exposure to chemicals and gasses causes unacceptably high rates of cancer among the local population. The locals can’t sell their homes, because there’s an oil refinery over the back fence, so they’re stuck in place, and they eat the long-term health costs of any nasty industrial accidents. In Norco, for example – the real historical Norco, named after the New Orleans Refining Company – there were two explosions at the Shell plant in 1973 and 1988 which killed multiple people – not just factory workers, but people living in the community, mowing their lawns and shit – and dumped nearly 160 million pounds of toxic chemicals into the atmosphere. Add in Louisiana’s history of racial injustice (“I watched the plantation land become machine land,” muses a dream-executive) and the aftereffects of Hurricane Katrina, and you have in capsule one of the deep evils of the modern day.

The game NORCO takes that history and spins it off into an imagined future, using the veil of fictionality to accentuate contemporary problems. Shell Oil is replaced by Shield, an oil company that “hid[es] the stars behind halogen and flame projected onto the sky every night.” Players move along the shore of Lake Pontchartrain, above New Orleans, with landmarks like the I-10 Highrise Bridge (pictured in the first image above) visible in the background. LeBlanc, a local detective, tells you about the bridge’s history, and its role in destroying local wetlands: “Then you got the Interstate Canal. The government built that to build Interstate 10. They let a whole lot of salt water into the swamp in the process. Killed off a lot of the trees.” There are even references to flooding events that link the town with Hurricane Katrina (“Three times this house has flooded.”) The destructive flooding is connected to the refinery through the association of fossil fuels and climate disaster. It speaks to a natural world disturbed, in turmoil. The destruction visited upon the town is only the destruction visited upon the broader environment. NORCO uses this reflection to link past and future, exploring Kay’s experience in the three floods in the past before presenting an option to learn about a fourth flood, which is yet to happen:

“The fourth flood will follow a slow hurricane and it will be a calamity. It will leave the entire region submerged as critical levees breach. There will be a massive blackout that lasts weeks. Much of the sewerage infrastructure will be damaged beyond repair. The embattled federal government will do nothing to assist. It will bankrupt the region. Small militant enclaves will form along the high ground of the Mississippi River. They will take to piracy and hijack commercial shipping vessels. Private mercenary forces will retaliate in kind. Slowly, industry will flee this hotzone. The Old River Control Structure will collapse from neglect and sabotage. The Mississippi River will again change its course.”

Remembering the past gives shape to the future. The lessons not learned give rise to the apocalypse, to the collapse of private enterprise and civil society. This in turn is the structure of NORCO. It is a future grown out of Louisiana’s past, a projection based on the lessons that have not been learned. It refracts those lessons into an imagined future – a future where nothing has been learned – a future that is really the same as our present.

NORCO also obviously explores the contrast between locals and the Shield corporation as two different ways of relating to the land. The locals live in Norco – it’s their home. It’s important to them as a place of residence. The corporation sees Norco as a site of extraction. It’s a commodity. They use the place up. When it’s exhausted, they’ll move on somewhere else. Shield is, in that sense, placeless. It doesn’t have a home or a natural habitat – it’s parasitic and mobile. It moves to where the money is. The locals are rooted in this place – that is, they’re literally rooted, stuck, with no easy financial pathway out, but even if they had that option, they have attachments, histories. They know the place. At the swamp’s noticeboard, the investigator LeBlanc says “Yeah alright, I remember this whole stretch from when I was a kid.” On the road, the narration describes how “The sky bleeds a color you knew as a child.” The locals see Norco as key to their sense of self. They are built up around the place, in collaboration with it. Its value, for them, is rooted in a shared past. The corporation is consumed by a ravenous now. It does not see in the future the obvious consequences of its self-destructive mining, and it sees no value in the past. It cannot connect with the land as co-creator. It is impersonal: without personhood. The power of the locals is that even as Shield devastates Norco, that devastation is woven into the selfhood of the people, like cuts in the bark of a tree. The destruction becomes part of their sense of self. It’s remembered in the history of the I-10, the memory of the floods, the toxic colour of the sky. These are disasters, but they’re also in some sense metabolised, absorbed into the lives of the locals. As memories, they become part of the fabric of life. “History has a lot of value in this place,” observes the robot Million.

That’s not to say that the locals are beating Shield – they’re clearly suffering. There’s no future in the town. Economic deprivation causes teenagers and young adults to leave for the city, for jobs, for better prospects. The town is increasingly made up of the sick and elderly, or the unemployed. People turn to religion and technology to help cope with their material conditions. A bunch of teenagers and dispossessed join a syncretic cult set up in an abandoned shopping center – the “mall nazis”, as they’re described, all call themselves Garrett (a Fallout reference?), and listen to sermons from the cult leader Kenner John (as in the Baptist). Mostly they sit around and smoke weed and play video games – they’re not dangerous, they’re disenfranchised. The cult lends a sense of structure and purpose to their lives. It tells them they’re going somewhere – tells them a story about who they are and what they mean.

Others, like Catherine and Duck, turn to technology. Technology in this game is not necessarily a good thing – every invention from concrete on tends to be framed as malicious. The highway is a form of violence: the interstate expressway “traces a scar down Claiborne Avenue”. Much of the descriptive language feels in the style of Allen Ginsberg or the Beat Poets – the city is made up of fences, strip malls, and smears of light. “Beyond the fence is drive-thru chicken, car audio, mattresses direct to you, water towers and powerlines and crumbling concrete and traffic signs, abortive landscaping attempts, unkempt shrubs, solar-fed Christmas lights weathered and forgotten.” The worst elements of this place tend towards the impersonal, the corporate. They refuse place and groundedness in favour of the transitory. It’s not a sit-down restaurant, it’s drive-through chicken. Attempts to connect with nature are “abortive”, and consumerist trash is littered about. It’s all rubbish bins and carparks.

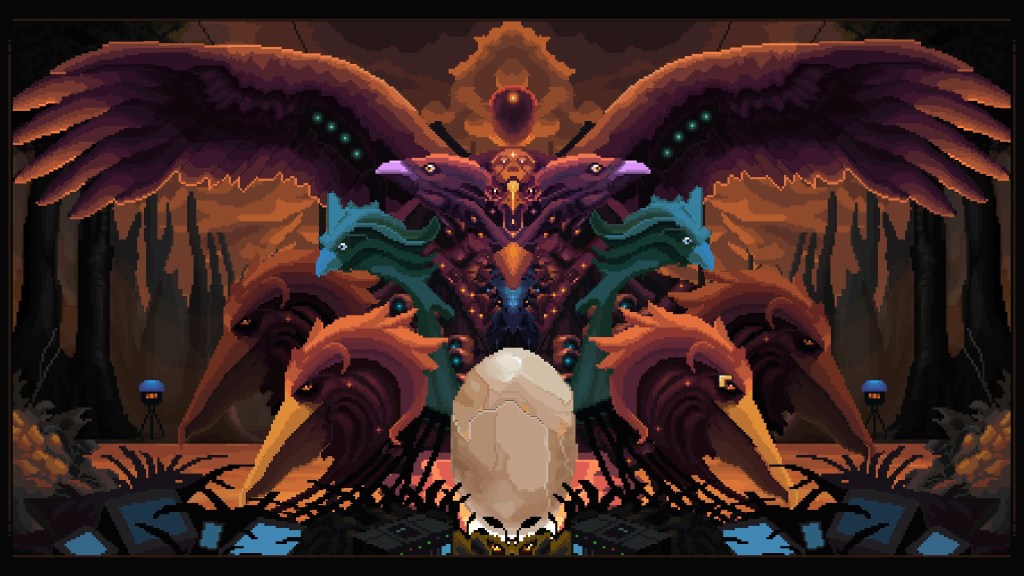

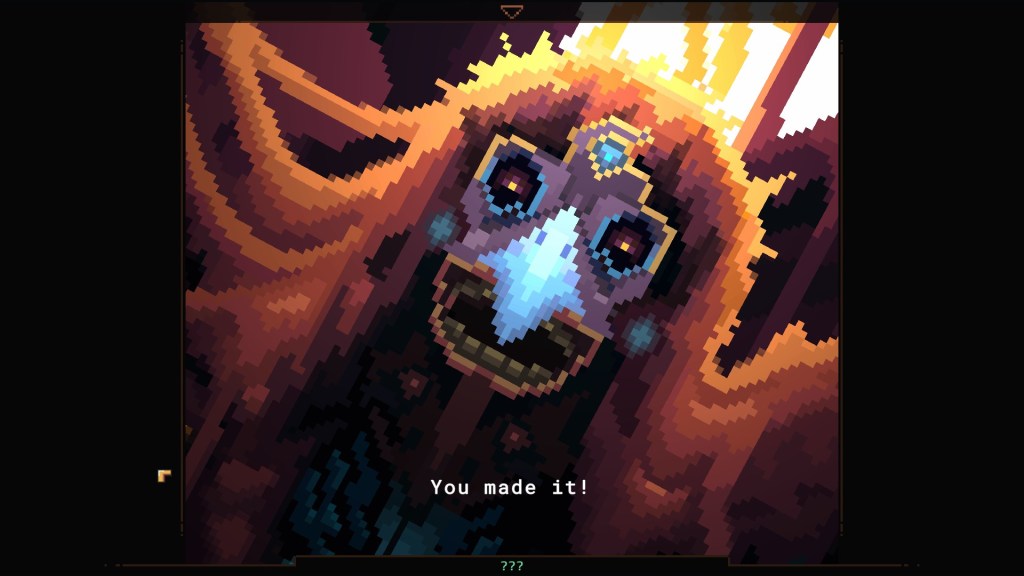

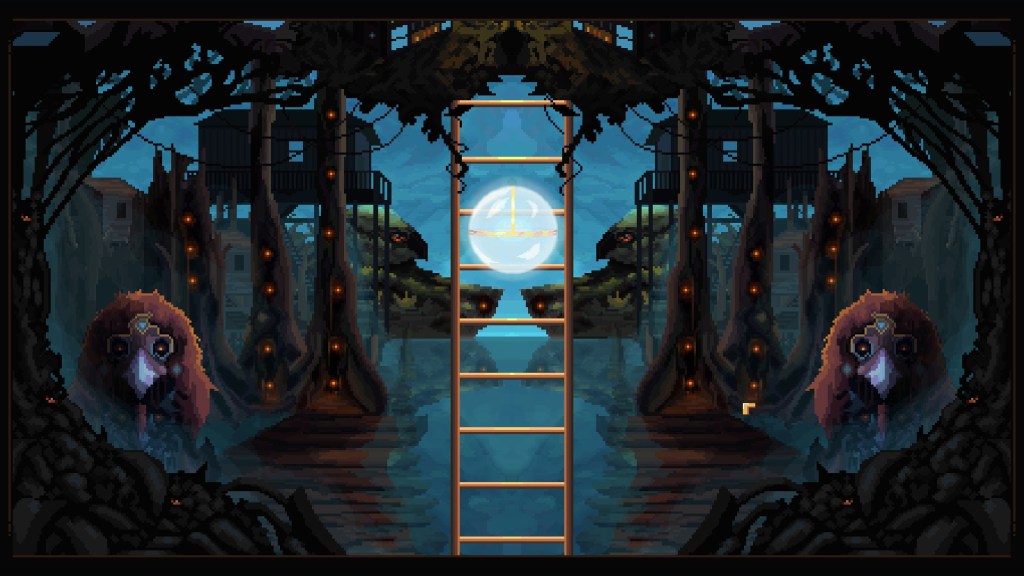

NORCO reserves a special hostility for digital technology. The “mall nazis” use augmented reality to spread bits of their gospel message around the town, and Catherine and Duck both use an experimental memory-storage technology, allowing them to store (and wipe) memories. As noted, memory in NORCO is sort of the basic operation of being human. It’s what distinguishes people in this game from factories and corporations. Catherine and Duck both outsource that responsibility to a machine, abandoning their intrinsic human burden to a computer. That technology in turn spawns the bizarre creatures that haunt the game. Superduck, a version of Duck’s memory that escapes into the internet, taps into the gig economy, hiring people to do odd jobs and collect trinkets. It’s – honestly, things get a little murky around here. Stuff starts to get weird. Technology and religion become part of the same hysteria, two expressions of the same form. There’s a priest that’s also a drone (“they’ll never decommission the drone priest, baby”), Superduck wants to capture an alien artefact, and the mall nazis build a spaceship to escape the planet, urged on by the same alien device. As you get onto the spaceship in search of your brother, the environment itself becomes syncretic – a combination of disparate features taken from incompatible sources. Aspects of the world are recast in an overtly symbolic way – they become icons, arranged symmetrically as if to communicate some sort of cryptic message. It’s set in the style of religious iconography but it’s all aliens and Superduck and the bayou. It’s electric LEDs and clouds and oil and the moon: “Metal-halide probing the river’s expanse. Coded patterns of warm sodium and cold LEDs winking, thinking, knowing.” Religion and technology whirl around each other, interweaving and recombining into some new hybrid form, some new genetic strain.

This is what I mean by awe – the scope of vision in this game, the complex language that sees religion and technology as merging forces, bending towards the same single point of self-destruction – two distractions from capitalism and the underlying ecological crisis. None of these forces are necessarily wrong or evil – aliens are real, and so is Superduck, and Pawpaw the Ditch Man might have actually heard from Mary Magdalene after all. When you go under the water in the bayou, you see impossible things. You swim through the window of a sunken house “and discover that there is no water beyond it.” Looking outside, “you watch as willow trees floating along the bank of the bayou leave the earth entirely, sucked into an insatiable purple sky.” There is a magic here, something unnatural, or supernatural, or from another world. There’s something magic happening in the bayou. “The lake and all of its sediment is infinite in its silence.” There is an insufficiency to our language and understanding. Shield digs away at the oil, and the poisoned, impoverished locals turn to their different solutions, and it’s all wrong, but through all of it, something – something – beats in the heart of the swamp. There’s still something out there, NORCO says. In the city, a planner speaks to Catherine shortly before her death. “But the stubbornness of nature is unmatched,” he says. “It drives the rest. In the end it drives our decisions. It forces them, you see?” You see?

[…] What The Swamp Knows in NORCO(deathisawhale.com, James Tregonning) […]

LikeLike