Like Halo, Assassin’s Creed is a wildly successful multimedia franchise launched in the 2000s and still producing new titles into the current day, with Assassin’s Creed Shadows (2025) serving as the fourteenth game in the main series. The original title, Assassin’s Creed (2007), traces its roots to the platformer by way of Prince of Persia: Sands of Time (2003), the previous project of creative director Patrice Désilets. Assassin’s Creed follows very closely after Sands of Time: it retains the Middle Eastern setting and the magical flavour, with the Prince’s time-winding dagger succeeded by the Apple of Eden, a mystical artifact with the power to control minds. It also shares the same uncomfortable relationship to the platformer label. It is not of a kind with classic platformers like Jak and Daxter or Crash Bandicoot, games that often feature a sort of ‘jungle gym’ setup – that is, where players must jump from one platform to another, and if they fail and fall they have to go back to the start. In Sands of Time and Assassin’s Creed, it is often difficult to actually fail a platforming challenge. They are less about precision movement and more about navigating around the various faces of a building. They are clambering games rather than platformers. Sands of Time features ‘action cams’ that will drop to dramatic angles to emphasise the drama and intensity of running along the side of a wall. In a typical platformer, that sort of unexpected, unwelcome camera movement might cause a player to miss their jump; in Sands of Time, it accentuates an action that is functionally un-failable.

Without pausing to define the genre with any further rigour, we can see a break between the platformer as focused on calculating difficult jumps (Celeste, Hollow Knight, Super Meat Boy) and a mechanically simpler platformer focused on the spectacle of movement. Assassin’s Creed is in this second camp. It is concerned with aesthetic and tone, with the detailed construction of a fictional world. It is concerned with the verity of its simulation. Again in marked contrast to Halo, and other shooters like Half Life 2, Assassin’s Creed allows you to skulk around simulated cities. The shooters exist in a fairly constant state of conflict: that is, enemy characters are usually present, active, and hostile. Assassin’s Creed depicts the city at rest. Guards will attack you if they see you break the law, but the law-abiding player has the run of the city. The game is therefore able to explore the social fabric of the world outside of the context of the warzone. The narrative goal of assassinating a band of villains becomes a tool for voyeurism, a mechanism for moving the player through different social environments. This is a common use of the assassin, as seen with the Hitman series or James Bond, both premised on an assassin travelling to some exotic location to kill people. Assassin’s Creed uses the assassin to explore the city as a continuous fictional space. It combines its open world with collectibles and missions scattered across the map. It encourages wandering. The substitution of platforming for navigating across the face of a building is contiguous with that focus on modelling the city: it is part of a practice of urban exploration.

This shift in focus is accompanied by a series of changes in level design and narrative structure. In Halo and Half-Life 2, the game level is best conceived of as a linear tunnel where the player must move from start to finish. There might be deviations for incidental secrets (or, on arriving at the finish, the player might be told to turn around and run back to the start), but they are functionally linear corridors with a strict sequencing of obstacles and events. Assassin’s Creed reconceptualises the virtual environment as a sandpit, as a loosely structured space for play. The narrative within that space is not entirely unstructured: certain missions and story beats still play out in a fixed order. At the start of the game, Altair, the main character, is stripped of his ranks and titles and sets out to redeem himself. His first major assassination is the weapons dealer Tamir in Damascus – and it will always be Tamir in Damascus. In other areas, the narrative is more flexible. Some missions are offered concurrently: after Tamir, the player can travel either to Jerusalem to kill the slaver Talal or to Acre to kill Garnier de Naplouse in his macabre hospital. The actual strict sequence of played events leading up to each assassination is also flexible. There are a series of hoops that the player must jump through, and a long list of collectibles and optional tasks, but no strict order as to how those are completed (or in some cases whether they are completed at all). The key story missions are therefore best thought of as gates locking off sections of the open world. Instead of asking when something happens, we are often better off asking where.

Obviously this is not to say that first-person shooters are disinterested in their setting. The Halo installation and Half-Life 2’s City 17 are iconic locations. The point is more to do with design philosophy. Assassin’s Creed orients the player towards the level, while Halo and Half-Life orient their players towards the event, which takes place in the level but has priority over it. A level in Half-Life 2 comes with a bundle of triggers, flags, and objects that collectively make up a narrative event. As the player, you move into an area, experience the event, and then the area is exhausted and you must move forward. The leftover space discourages lingering. It is stagey, theatrical, like a darkened set after a show. It’s eerie. The level has little life after the event is complete. Assassin’s Creed offers a continuously simulated space where large narrative set-pieces sometimes occur. The level has priority over the event: the event is a temporary interference, a brief festival, whose primary function is to unlock more of the level. Halo and Half-Life adhere to the structure of film. They both offer a sequence of narrative events that take place in a linear fashion. They are so many beads on a necklace. Assassin’s Creed prioritises space, setting the level over the event. It is normal in Assassin’s Creed to cross back and forth over certain areas. Gates, archways, buildings – ah yes, here again. You exist in a network, in an urban web. The organising principle of ‘when’ is replaced by the principle of ‘where’. There is still a loose narrative framework, still a sense of linear progression, with further areas opened up to you as you complete certain narrative tasks (kill Tamir and you can go to Jerusalem and Acre), but the underlying logic has shifted from the filmic vision of Halo and Half-Life 2 into nodal digital terrain.

The clambering, exploratory platforming of Assassin’s Creed is therefore best understood as a response to this change in design philosophy. It is a shift in play to accompany the shift in space: as linear levels are replaced with the sandpit, closely choreographed linear challenges are replaced by wandering, meandering, crossing back and forth. The platforming in Assassin’s Creed prefers exploration over skill-based challenge or win-loss gameplay. Those latter features still characterise other aspects of the game (such as combat), but not navigation of the city. Assassin’s Creed deepens our experience of the city by allowing us to exist outside of the immediate demands of conflict and encouraging exploratory, unstructured movement, free from any intensive skill-based demands. That mechanical shift is paired with a narrative focus on uncovering forgotten, mysterious history. Assassin’s Creed, like Sands of Time, draws on Western fascination with the Middle East as an exotic site of mystery. In the wake of WWI, the defeated Ottoman Empire lost most of its territory, particularly through the Middle East, which was divided up between Britain and France into a series of protectorates. Britain took Egypt, and in 1922 the British archaeologist Howard Carter discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun. The opening of the tomb was swiftly followed by the death of Carter’s sponsor, George Herbert, the Earl of Carnarvon, leading to rumours of Tutankhamun’s curse. The power of these rumours seems to be in how they articulated the political relationship between Egypt and Britain. Egypt was a newly acquired territory. It held a clear place in the British imagination: ancient, mythic, mysterious. The Egyptians, for their part, were not interested in being controlled, and protests and riots were violently repressed by British military. The discovery of the tomb and the high-profile death of Carnarvon seem to embody the British narrative of Egypt: mysterious but dangerous, a new, hostile resource, holding secrets that it would not surrender easily. That was the basic conception of Egypt (and the Middle East more broadly) throughout the twentieth century, underpinned by a long tradition of orientalism and reinforced most recently in the 80s and 90s by films like Indiana Jones and The Mummy. On September 11, 2001, al-Qaeda terrorists hijacked planes and flew them into the Twin Towers, again reinscribing the Middle East as a dangerous, mysterious place where hidden assailants lurked and plotted. Assassin’s Creed draws on that cultural context, building its narrative around the motif of uncovering the hidden past.

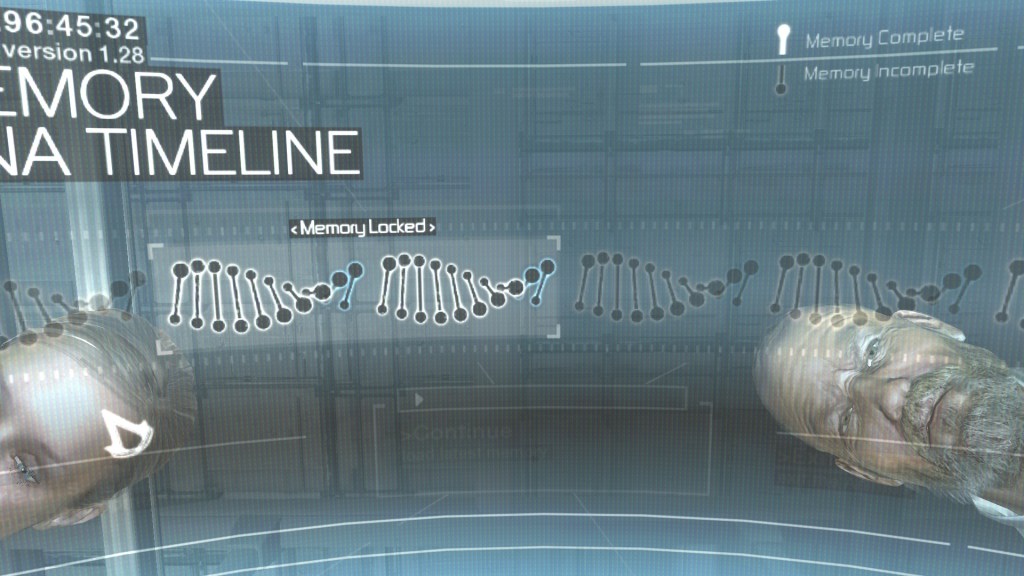

Again following Sands of Time, Assassin’s Creed uses a frame story. In Sands of Time, the game is a story the Prince is telling to a princess, inverting the setup of Arabian Nights. If a player dies or has some other Game Over, the Prince says words to the effect of – hang on, that’s not how that happened, and the scene restarts. Assassin’s Creed slightly tweaks that formula, bookending its Middle Eastern sequences with a framing narrative set in the modern day. In this framing narrative, experimental new technology allows people to explore the genetic memories of their ancestors, essentially reliving their ancestors’ lives. The mysterious Abstergo Corporation has kidnapped Desmond Miles, a bartender, and forces him to explore the memories of his twelfth-century ancestor Altair, who Abstergo believes came into contact with an ancient artefact, the Apple of Eden. Abstergo wants to find out where Altair hid the Apple in the twelfth century so they can retrieve it in the present day. The Middle East here plays its typical role, concealing some secret, magical object that can only be retrieved by exploration, by delving into the historical record. The framing device also means that the Middle East is always presented as a forgotten or secret past: it is never ‘now’, never contemporary, but always something the player is looking back on. While the setting is tied to a specific historical moment (the end of the Third Crusade in 1191), the game blunts its post-9/11 political charge by reframing the Crusades as a shadow battle between two occult societies, the Assassins and the Knights Templar, who are positioned as secret orders warring throughout history. The modern day sequences reveal that Desmond Miles is associated with the modern Assassin Order, while Abstergo is the corporate front of the Knights Templar. While the game is about exploring the past, in that sense, it is not necessarily concerned with historical accuracy. It invents and unveils an alternate history to give the effect of pulling back the curtain, showcasing secret societies and global conspiracies as if to say – this is the real truth, the stuff they’ll never teach you about in school.

That alternate history satisfies the player’s desire to discover and learn, to uncover some hidden truth about the Middle East. It dovetails with a game structure focused on exploration rather than skill-based platforming. Both game structure and narrative are concerned with a process of discovery. They embed the player into a simulated social fabric and encourage exploration and learning. There is a twin emphasis on incidental social encounters and realistic reactions. You can listen in on the discussions of strangers to gather clues about your targets, or pickpocket evidence from Templar agents. Alternately, if you shove past a woman carrying a jar on her head, you might cause her to drop it, which will make her shout and point and summon the guards. The game allows the player to conceal their violence, tapping into contemporary fears around terrorism and the hidden combatant, but also facilitating an embedded spatiality. You exist within the city, within the social fabric, which means within the constraints of certain social norms. To be clear, from today’s perspective, the game’s efforts are a fairly bald, clumsy attempt at modelling a social environment. Key figures (like the woman carrying a jar) are repeated so frequently as to become stock characters, motifs or patterns rather than individuals with any sense of humanity. Game mechanics are often limited and repetitive: eavesdropping and pickpocketing are two of only three possible tools to gather clues for each assassination. The game is something of a blunt instrument. Its power is not in the scope of its gameplay but in how it structures its space.