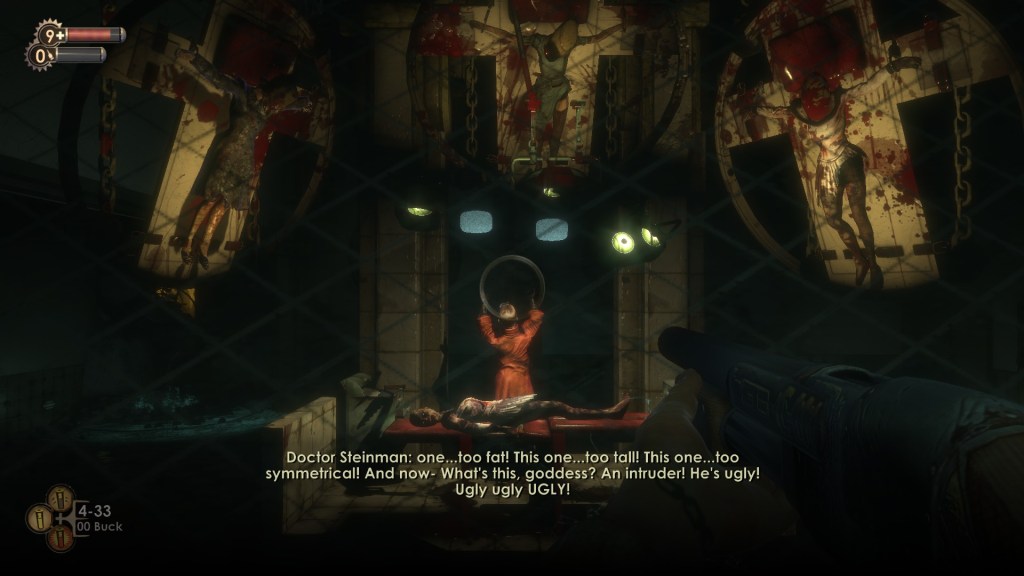

“What can I do with this one, Aphrodite? She WON’T. STAY. STILL! I want to make them beautiful, but they always turn out wrong! That one… too fat! This one… too tall! This one… too symmetrical! And now- what’s this, goddess? An intruder! He’s ugly! Ugly ugly UGLY!”

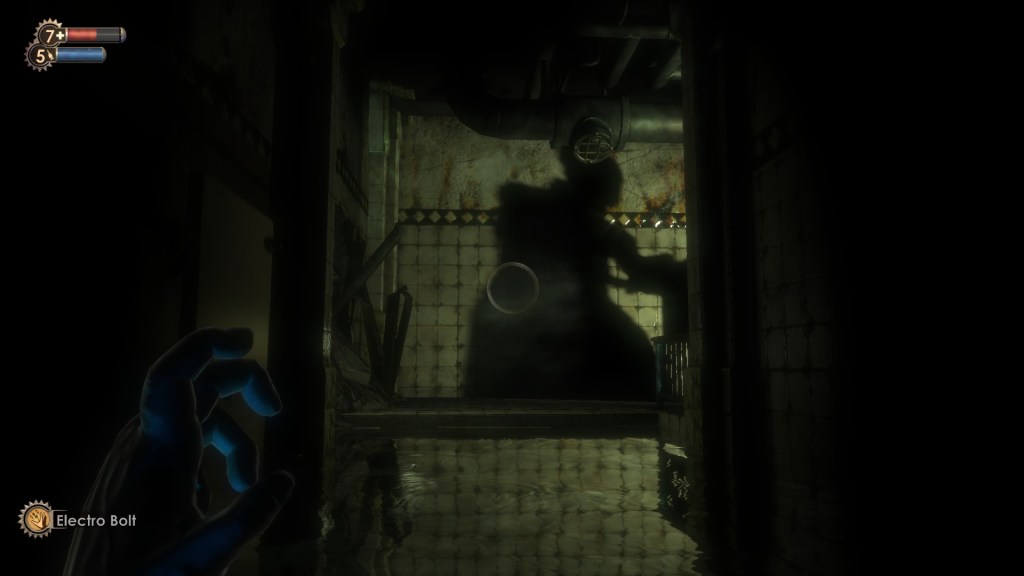

BioShock (2007) is at all times a self-consciously theatrical game. Many of its villains are artists or creatives (in Fort Frolic, for instance, Sander Cohen has you murder his past acolytes and photograph their bodies for his art installation), but more fundamentally its basic aesthetic is rooted in the first half of the twentieth century. It’s a throwback. Against the cultural backdrop of Avril Lavigne and Jackass, BioShock was about suits and cigarettes, roses, music halls, Prohibition, art nouveau, and pneumatic tubes. It drew from the science fiction of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells, and stopped just shy of George Orwell. It’s The Great Gatsby by way of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. There’s something reactionary in that, something escapist, but self-consciously so. BioShock is built around artifice. It’s theatrical. It deals in moustache-twirling villainous speeches, as with the introduction to the J.S. Steinman boss fight, quoted above. The player discovers Steinman behind a reinforced glass window: you can watch but not interfere, not until he completes his dramatic monologue. Steinman’s introduction draws on the mechanics of the theatre. The reinforced glass window is framed by cracked marble tiles, a parody of the proscenium arch. As Steinman gestures to each of his failed, butchered experiments, they are lit by floodlights, perfectly on cue. There’s no diegetic reason for those experiments to be lit up – it’s a spectacle for the viewer. It’s theatre. It’s also very graphic horror: Steinman punctuates each of his comments by slashing at his latest patient/victim with his surgical tools, accompanied by screams and great gouts of blood. BioShock tempers its reactionary nostalgia through a combination of horror and theatricality. They have a distancing effect: they remind the player that this alternate vision of the world is not positive, not idyllic – not real.

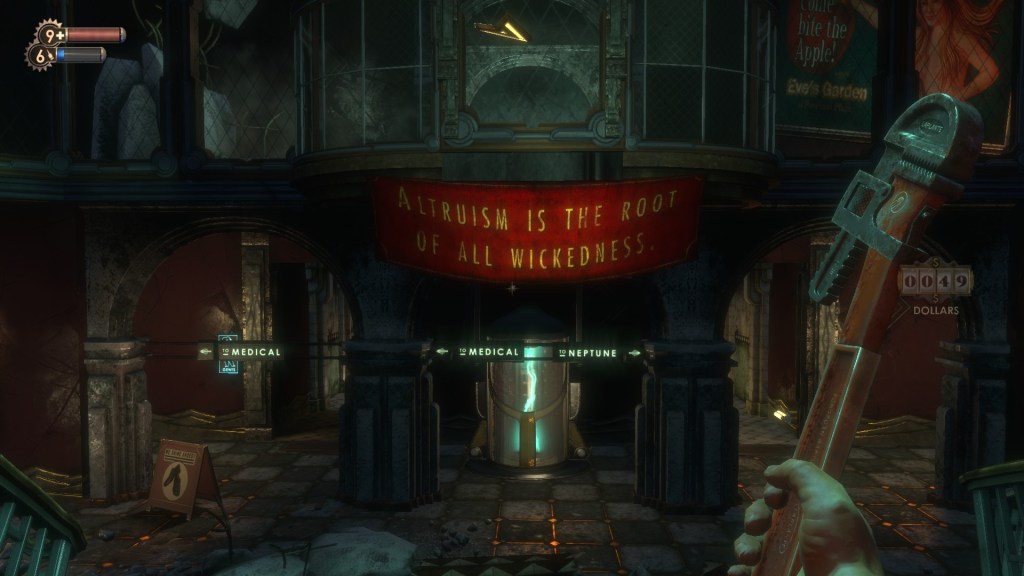

The retro aesthetic is also built into BioShock‘s temporal framing. While the game is set in the 1960s, it has the main character rediscover an underwater city, Rapture, built twenty years earlier, in the 1940s. The player, like the main character, looks back at a place from an earlier time. BioShock uses that ‘looking back’ to explore the philosophy of Ayn Rand, recast in the fictional form of Andrew Ryan, Rapture’s overlord and founder. Ryan operates a city free of ethical constraints or restrictions, where the artist and the scientist can forge ahead, unfettered by conventional morals in pursuit of their craft. He articulates his vision as the “Great Chain of industry” – essentially free market economics – arguing that “it is only when we struggle in our own interest that the chain pulls society in the right direction.” What happens instead, of course, is madness and the collapse of civil society, as figures within Rapture pursue self-interested financial ends that have deleterious social effects. Addictive substances like cigarettes and alcohol are littered throughout the game, and a discussion of ‘Adam’, a drug that allows people to modify their genetic code (and shoot bees from their fingers), treats addiction as a viable business strategy. “You need more and more Adam just to keep back the tide. From a medical standpoint, this is catastrophic. From a business standpoint, well…”. This is the inherently self-destructive nature of Ryan’s philosophy. From a commercial perspective, it makes sense to cultivate dependency or addiction in your customers. It keeps them coming back. It’s socially destructive, but commercially sound. This type of basic disregard for the broader social fabric, underpinned by Ryan’s Randian philosophy, swiftly leads to the collapse of civil society. It results in figures like Steinman, a sort of early plastic surgeon, whose cosmetic improvements become mutilations and then outright murders. In his unfettered pursuit of beauty, his human canvasses are reduced to biological material. He sets his individual, personal goal, the pursuit of his artistic vision, above the wellbeing of his patients. Steinman embodies BioShock’s critique of Ayn Rand and her individualistic philosophy: try as we might, our individual goals and achievements depend on those around us, whether to support bodily needs like food and shelter, or, as with Steinman’s subjects, to provide the raw material for craft. Rapture is a city trying to escape from the world, pulling back from social entanglement to liberate, quote-unquote, its great minds. The criticism of BioShock is that such liberation does not exist. Even in the reclusive city of Rapture, Steinman’s work depends on social entanglement. He needs people who want to look beautiful, and a broader society in which the concept of beauty exists and holds social currency. The final, disastrous form of Steinman’s work only expresses the dehumanisation that was inherent in its premise. He butchers his subjects because he subscribes to a philosophy that teaches disregard for other people, for the social fabric that he is embedded in and relies on.

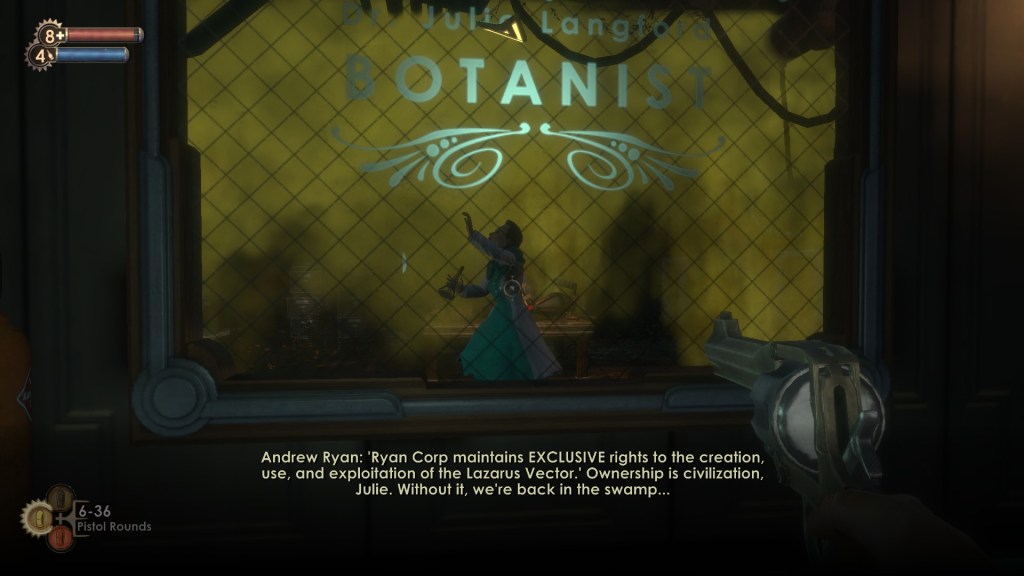

The philosophy of BioShock is well-travelled ground – part of the popularity of the game is its explicit engagement with these philosophical concerns. It was for many people their first exposure to Ayn Rand, objectivism, philosophy in general, and even the concept that video games could grapple with such things. Today, the thing that stands out to me is how BioShock deals with artifice. The type of reinforced glass window that frames Steinman is used routinely to introduce key mechanics or characters. Most major characters (including the two main villains, Andrew Ryan and Fontaine) are introduced behind unbreakable glass, as is the Big Daddy, one of BioShock’s most iconic creatures. Key game mechanics like the fireball mutation are similarly taught from behind glass. When you find the fireball mutation, you’re in an office, with demented splicers battering on the windows. You’re told to ignite an oil slick, which runs under the door and around to the splicers, setting them on fire and ending their attack. Reinforced glass is used regularly in this way, as both tutorial and character introduction. Sometimes it’s drawn overtly into the narrative, as when Ryan murders the botanist Julie Langford. Langford is in her office (behind reinforced glass), and Andrew Ryan floods her office with poison. In her final moments, she uses the glass to scrawl down the passcode to her safe, which holds key information allowing you to proceed through the game. These are all theatrical moments. They have a level of artifice, of scriptedness. The game uses unbreakable glass to direct the player’s attention, to deliver key information without taking away control of the main character (as might happen, for instance, in a cutscene).

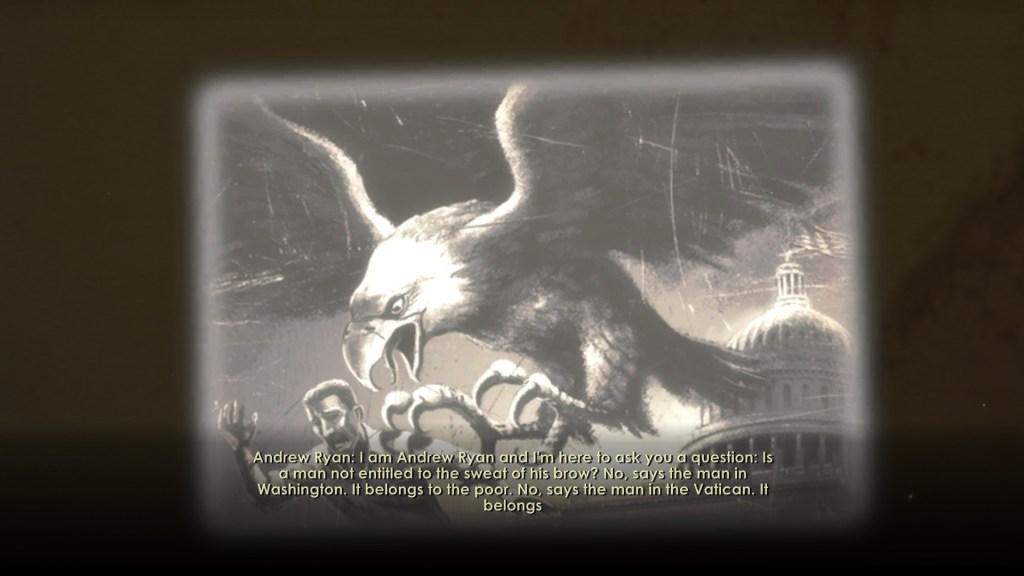

The reinforced glass technique is only one of the more overt types of artifice in BioShock. More broadly, the game uses techniques that tend towards either horror or the lecture. Early in the game, walking towards a T-junction, the player sees a splicer run across the passageway – an early vision of hidden horrors. The game often uses light to throw large shadows on the wall, warning of splicers hiding further ahead. In the morgue, thrown light reveals a splicer experimenting on a corpse down the end of a hall. If the player runs in, the splicer vanishes: as the player leaves, the splicer leaps out of a secret door and attacks. The groves of the Saturnine cult are signposted by wood or straw effigies that burst into flame as you approach – it’s all very theatrical, overtly and artificially so. When you first discover the shotgun, someone switches off the lights, leaving a small, circular pool of light in the centre of the room. Splicers run out of the dark and attack you, forcing you to fire at close range – in essence forcing you, teaching you, to use the shotgun. These horror techniques are juxtaposed against the lecture – not just unskippable scenes of dialogue, but educational pieces where characters set out to tell you something about the nature of your environment. The most obvious example is the introduction to Rapture: as you descend in the bathysphere, a literal film screen descends over your glass viewport, and a video of Ryan outlines the philosophy of Rapture.

“Is a man not entitled to the sweat of his brow? No, says the man in Washington, it belongs to the poor. No, says the man in the Vatican, it belongs to God. No, says the man in Moscow, it belongs to everyone. I rejected those answers. Instead, I chose something different. I chose the impossible. I chose – Rapture.”

As Ryan pronounces the name of the city, the video screen rises, and the player has their first view of the city – the underwater metropolis, the art nouveau New York. As you sweep through the city, Ryan’s monologue continues, and he outlines the philosophy of Rapture, “a city where the artist would not fear the censor, where the scientist would not be bound by petty morality, where the great would not be constrained by the small.” It’s an artificial moment – the length of the video deliberately timed against the bathysphere’s speed of travel, the screen blocking off the outside world to curate that impactful first view of the city. Artifice is the repeated motif that binds horror with Andrew Ryan’s lecturing. It links the nightmare of what Rapture’s become with his philosophical vision. You start with this grand idea of everyone working for their own self-interest, and end with crazed splicers jumping out of hidden doors in mortuaries.

There is also a level of artifice in the game’s main twist. As is, again, well-trodden ground, BioShock has a twist ending where it emerges that your actions are driven by a secret compulsion. Your companion over the radio, Atlas, has been directing your actions with the control phrase ‘Would you kindly’: you think that you’re making your own decisions, but you’re actually under a form of mind control. The reveal emerges at the climactic point of the game, as you finally arrive at the office of Andrew Ryan and murder him. He outlines the psychic control mechanisms and reinforces the kill order, screaming “Obey!” as you bludgeon him. Atlas soon after reveals himself as Ryan’s adversary, the nefarious Frank Fontaine, and the game moves into its final sequence, where you break free of the mind control and defeat Fontaine as well. Strictly, the whole routine of Fontaine disguising himself as Atlas is unnecessary. Fontaine originally takes the alternate identity as part of his machinations against Ryan, but there’s no need for him to wear the disguise in front of his mind-controlled minion. He could simply announce his instructions without all the pageantry and nothing would change. In fact, Fontaine goes to fairly extreme lengths to maintain your ignorance. For the first few levels of the game, while masquerading as Atlas, he has you running around trying to rescue his wife and child from a submarine. The wife and child do not in fact exist, and after the reveal, Fontaine makes fun of you for imagining that his concern was real: “I really wound you up with that wife and child bit.” Again: there really is no reason for Fontaine to put on this whole routine. He can simply command the main character to do whatever he wants. The disguise is best understood as a narrative device that makes the player invested in helping Atlas, strengthening their sense of betrayal on the other side. It has narrative utility – it makes for a good story. It also folds into the game’s broader critique of Ryan’s philosophy. The concept of the individual working for their own interest misunderstands how our interests can be manipulated, redirected. It misunderstands the basic nature of advertising. In BioShock, you might think you’re acting towards your own ends, but you’re being controlled. Your consent has been manufactured. Ryan’s Great Chain is more aptly understood as a tool by which corporate interests capture and control the individual consumer.

The good and bad endings of BioShock tie back into whether the player recognises and rejects the destructive nature of Ryan’s philosophy of self-interest. Throughout the game, mutated harvesters – children, little girls – roam around collecting genetic material from dead splicers. Atlas instructs the player to harvest these children, killing them but growing more powerful. Another character, Tenenbaum, suggests that you rescue them, ending their mutation and receiving less immediate benefit but – you know – also not murdering a child. Rationally, the self-interested thing to do is to murder the children and receive the maximum possible benefit. That approach, the Andrew Ryan approach of quote-unquote rational self-interest, leads to the game’s bad ending, where you take control of the city, and then take over a nuclear submarine. Self-interest destroyed Rapture, and it’ll destroy the world too. Saving the children – acknowledging our shared humanity and our moral obligation to each other – leads to the good ending, where the protected children grow up, live normal lives, and eventually attend at your deathbed. In voiceover, Tenenbaum tells you that your reward in this ending was family. You become integrated into a reciprocal social unit that gives meaning and structure to life. There’s more to life than tangible, material gain, BioShock says. It’s not about rational self-interest, it’s about human relationships, about our connections with each other. It’s about the decision not to murder a bunch of children even if it materially benefits you – how’s that for a trolley problem?

BioShock as moral thought experiment is framed with a great deal of pomp and pageantry, a lot of artifice, which maybe robs some of its staying power. It asks the player a philosophical question – self-interest or social interest? – but sets the question in a world where self-interest has destroyed an entire city. It’s leaning on the scales here. It has an opinion. It’s argumentative rather than exploratory. It wants to put across a set of ideas and values about the world. It uses the structure of inviting participation in a philosophical thought experiment, but it’s really more of a carnival ride. It’s closely constructed, heavily rehearsed, like a street evangelist with their canned gotcha questions. The game’s scriptedness feeds into that dynamic. All the reinforced glass, the scenes where you’re technically in control but practically obliged to sit and listen – like its villains, BioShock lectures. It gives you the appearance of control while it’s really directing and instructing. It is deeply artificial, and it draws attention to its own construction, to its constructedness. While its stagey, theatrical gameplay still holds a sort of campy charm, it puts forth the idea that video games can be an appropriate mode for exploring philosophical questions. It presents itself as evidence for that claim. Its staying power I think is not in the specific question it asks, or the way it frames the conversation, but in how it demonstrated that these questions were open for discussion – that they were within the realm of the video game.