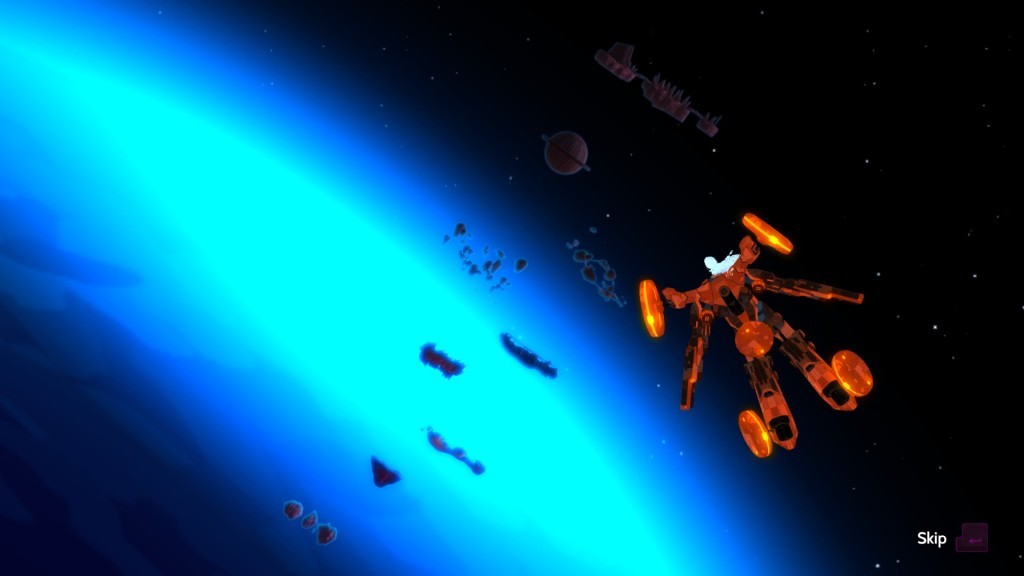

Furi is a 2016 game created by The Game Bakers, a French company working out of Montpellier. It’s essentially ten boss fights in a row, Shadow of the Colossus style. Or maybe eleven boss fights, if you have the DLC. Or maybe nine boss fights, depending on the ending you choose. Or – let’s start this again. Furi is a 2016 game where you try to escape a prison by fighting through a gauntlet of bosses. As you proceed through the prison, you learn more about the world and why you were imprisoned in the first place. It turns out that you were a scout sent to scope out Earth on behalf of an alien military force, and you were caught and stuffed in this prison before you could return to the mothership and initiate the invasion. At the game’s climax, after escaping the prison, you decide whether you will start the invasion as planned, or whether you will abandon that goal and fight your own people to defend Earth. If you choose to defend Earth, you have to fight the mothership, which serves as essentially an optional final boss leading to the ‘good’ ending.

Regardless of whether you choose the good ending or the bad ending, when you finish the game, you’ll get a score. It tells you how many times you’ve died, how long you’ve taken, and gives you an overall letter ranking. Oh – there is also technically a secret ending before the sixth boss – you stop in a garden with an angel, and she asks you to just stay and enjoy the garden, and stop trying to escape. You can accept her offer, ending the game – but it’s treated as a premature ending, a secret ending, rather than a proper, normal ending resulting from a full playthrough. For example, you don’t receive a letter ranking if you take the angel’s offer. Structurally, this ending is presented as a side-path, an early branching option that closes the narrative arc. From a narrative perspective it’s arguably just as valid as either of the other two endings, but in terms of gameplay, it’s treated as premature, incomplete. We specifically don’t see such a distinction made between the other two endings: you can choose to fight the mothership, or to start the invasion, but either way you’ll receive a letter ranking and a breakdown of your gameplay statistics. The game even gives you an extra time and death allowance if you choose the ending with the additional boss fight. Again, all three options are equally valid in a narrative sense, but in a gameplay sense, you only get the full conclusion of the game when you play through to one of the final main endings.

So it’s fair to say that the game ‘wants’ you to play through to the final choice with the mothership. It doesn’t mind what you choose, but it wants you to get to that choice. And that creates some interesting resonances within the narrative. When you return to the mothership, you learn that the invasion was waiting on the findings from your scouting mission – that it couldn’t begin until you’d returned with your report and confirmed that the planet was worth invading. But if that’s the case, why go back to the mothership at all? If you’d stayed in the angel’s garden, wouldn’t that have stopped the invasion just as efficiently? Maybe you could make some limited arguments as to why you have to go and destroy the mothership – for example, maybe it would have just sent another scout to Earth in your place. The mothership refers to you as ‘a’ rider, rather than ‘the’ rider – implying there’s more than one of you – so maybe it would have sent a second scout. However, even if it did, there’s no guarantee that this other scout would have found evidence that Earth was worth invading. Your own report returned inconclusive results – and you were on Earth for long enough to destroy an entire civilization before getting caught and imprisoned. So maybe the mothership would have gone somewhere else. Plus, if there are multiple scouts, they’re presumably out scouting several different planets – the mothership describes Earth as “your target planet” – so maybe one of the others would come back with their own positive result and the mothership would just leave.

Ultimately, there’s no real way to know the answer. We’re trying to backfill plot elements that the game didn’t bother to explain. What we can say is that when the Stranger (the main character) decides to fight the mothership, his escape becomes less about his own freedom and more about protecting Earth from dire consequences. The fights take on a tragic hue, where he’s fighting and killing his jailers essentially for their own good – or at least for the good of their species. Again, it creates some interesting resonances within the narrative. If you ignore the angel when she asks you to stay, she will fight you, but she’ll be frustrated and sad throughout the fight. She’ll very explicitly tell you, repeatedly, that she doesn’t want to fight. Her feelings mirror those of the good Stranger: he doesn’t want to fight either. The angel is trying to keep him in to save the world, to stop him from destroying everything, but he’s trying to get out to save the world, to stop the mothership from destroying everything. Similarly, the fifth boss is a knight who originally led the mission to capture you. When you first enter his arena, you see his son, who runs and hides. The knight says that you cannot defeat him because he’s fighting for his son. He draws strength from that. By contrast, he sees you as being alone, and therefore less powerful: “I look at you, Stranger, and I see nothing. Desolation. Death. You are alone.” Again, if the Stranger is trying to save the world, those words ring with a bitter irony. You’re trying to do the right thing, you’re fighting on behalf of humanity, and yet you have to kill him to do it. The knight is correct: fighting for a greater cause does give you strength. You’re fighting for his son just as much as he is.

At this point, we should probably stop to ask the glaring question. We’ve talked about the implications of the good playthrough without establishing the Stranger’s motivations for acting in such a way. From the player’s perspective it’s not a hard decision – when you’re asked if you want to Do The Bad Thing or Do The Good Thing, most people pick the Good Thing. But is that consistent with the Stranger’s psychology? What caused him to change his approach, his values? Let’s just recap the story briefly, just to make this point clearer. At the start of the story, the Stranger is a scout for this alien race. He arrives on Earth, and the land under his feet burns and blackens. He is a corrupting force – we see this effect both once he escapes from his prison, in the brief interlude before he flies up to the mothership, and in one of the jailers, a deranged, contaminated, radioactive diver. After destroying a bunch of stuff, including an entire human civilization, the Stranger is eventually captured and imprisoned. He is tortured regularly by his jailer, and then eventually freed by the prison’s architect. His subsequent battle to escape from the prison makes up the bulk of the game. Where, in all of that, does he decide that he should actually help humanity?

To some extent the answer doesn’t matter. Players can put this turning point wherever they want, or even just ignore the issue altogether. In fact, arguably we’re not supposed to be thinking about the Stranger at all. Arguably the architect has the game’s primary emotional arc. After designing the Stranger’s prison, the architect was forced to take up residence as one of its jailers, leaving his daughter alone on Earth. He frees the Stranger in an attempt to get back to his daughter, even though he recognises the very real risk that the Stranger might immediately go off and destroy the world. After the contaminated diver, he muses to himself “Destruction of the world on one hand. But on the other… what about my world?” In a grotto in the angel’s garden, he mutters “I need to be alive again. Even if I die a minute later.” That’s a compelling arc.

And even the fights speak to the architect’s arc. Both the knight and the architect are fighting for their children. The knight is fighting to protect his child, and humanity more broadly, while the architect is fighting to be reunited with his child, even at the very real cost of the end of the world. Similarly, the final fight of the prison is against a young girl – maybe in her teens, maybe her twenties, but obviously not a good fighter. She’s usually considered the weakest of your opponents. As she dies, she asks you to hold her hand. It’s heart-wrenching stuff, but it almost feels harder for the architect than for the Stranger. Again, the Stranger doesn’t have a reason to care about any of this. He doesn’t care whether he’s killing children or old ladies or whatever – why should he? But for the architect – in pursuit of his own daughter, he’s had you kill a father in front of his child, and now he has to watch you kill a child as well. He destroys the characters most analogous to himself and his daughter, suggesting that ultimately his ‘love’ is destructive both to himself and the person he cares for. He doesn’t feel bad about it, though. Instead, he blames the people who set up the prison: “Why did they let her join? How many were they prepared to sacrifice? She’s an overconfident, idealistic child, who dreamed she could save the world. She’s an amateur. Short-sighted. Plain stupid, if you ask me. What a waste.” There’s no sense of responsibility or accountability here. He doesn’t feel bad for freeing a dangerous prisoner and allowing him to murder a child. He blames the people who designed the prison and set up the jailers.

And it’s fine that the architect is such a scummy character. From a narrative design perspective, that’s not a bad thing. It’s interesting. But it raises again my question from before: why does the Stranger decide to be good? He’s an alien being with an evil mission. He’s captured and imprisoned by a bunch of heroes, and then released by a selfish, evil man who wants to see his daughter again even if it immediately kills her. The question here isn’t so much about individual events of the plot as it is about the plot’s arc. In the ‘good’ ending, a bad man sets free a dangerous, world-ending prisoner, fully understanding the apocalyptic consequences of his actions, but luckily the prisoner decides to be good and not end the world. All of the actual heroes are dead – the angel, the father, the child – and the bad guy gets to swan off with his daughter and zero consequences. Cue curtain.

So here’s my point about the Stranger’s moment of change. You can locate it wherever you like, using whatever story beat you believe justifies the transition. But there’s still a broader question about why that transition happens – not from a psychological perspective, but in terms of narrative and plot. When I played through Furi, I chose the ‘bad’ ending. It seemed like a better resolution. The architect makes a terrible decision, gets a bunch of good people killed (including, again, a literal child), and causes the destruction of the entire world. He sees his daughter again, briefly, and then everybody dies. The Stranger shouldn’t magically turn into a hero just to get him off the hook. Decisions have consequences, and the architect should wear his. The bad ending is the good ending – and if you don’t agree, I’ll fight you, right after I’ve dealt with this mothership. Fuck I hate bullet hells.