Enslaved: Odyssey to the West is a 2010 sci-fi action game based around the 16th century Chinese novel 西遊記, or Journey to the West. It sort of plays like an early PS3 version of Horizon Zero Dawn: there’s been an apocalypse, there are mechs everywhere, and nature has grown up and over the ruins of our urban wasteland. It’s a curious game for a number of reasons – as an early example of motion capture in video games, as a collaborative effort involving established film industry figures like Andy Serkis and Alex Garland, and as a game built around classical Chinese literature. It also has a lot to say about masculinity and gender in the late 2000s.

Enslaved is something of an enemies to lovers story. Monkey, played by Andy Serkis, is a wild man living in the ruins of civilization. The story opens with him escaping from slavers, along with a second prisoner – a tech whizz named Trip. Trip subjects Monkey to a slave’s headband and forces him to escort her home, initiating a hostile relationship that softens over the course of the game as the pair grow and develop together. Their mutual antagonism is set aside in favour of romantic connection and genuine interdependency, albeit with the sort of late 2000s visual symbolism that feels like it was pulled from Shrek.

Even from that overview, you can see that Monkey and Trip are each built around a key theme or idea. Monkey represents the animal: he is a crude, brutish man characterised by physical strength. His animal name is emphasised through costuming – his gold belt is tied off long at the back, hanging down in visual reference to a monkey’s tail. Trip, on the other hand, represents technology. She controls Monkey through the slaver’s crown, and her support actions during gameplay relate to hacking and reprogramming. There are fewer immediate visual references: the most prominent is her surveillance drone, artfully made up to look like a feather in her hair. Of course, the characters are not exclusively split between the animal and the technical. Both have elements of crossover. The surveillance drone is a mech shaped like a dragonfly, imitating the natural world, and in combat Monkey draws on technology like his stun gauntlets and blast rod. Those elements of crossover are, in essence, the question the game is trying to address. What is the ideal relationship between the physical and the technological, between body and computer? Where does the balance lie? The apocalyptic setting is evidence of imbalance – evidence that the world has already got it wrong. It’s through the relationship between Monkey and Trip that the game sets out its vision of how to do it right.

The way that these characters are gendered also points to contemporary anxieties about the relationship between men and technology. Trip is something of a cipher in this game – she’s not really a character in her own right. She’s a projection, a complicated object of desire. As a symbol of technology, she is a source of attraction and revulsion for Monkey, and, implicitly, for men more broadly. Enslaved is concerned with the disempowering effects of technology – with its potential to emasculate, to undermine or take away masculinity. It’s a video game worried about how video games aren’t all that manly. Back in 2010, we were living in the age of Gladiator, Lord of the Rings, 300. There was a real focus on the masculine body in media, on manual, physical action as a source of power and agency. The related fear was that computers and video games were (or are) somehow degenerative, that they’re taking away from the potency of maleness. We see it in how that period depicted the office – in Fight Club, Wanted, and even The Incredibles, the corporate office is a site of male impotence, with harsh blue colour bursting from the computer screen or from fluorescent tube lighting overhead. Contrast Edward Norton’s pasty ass against the weathered, tanned action heroes of 300 or Gladiator. Fear and fantasy: two sides of the same coin. In Enslaved, the same basic fear is present, but it’s a little more coded towards video games. Let’s talk about Pigsy.

Pigsy is a character encountered in the game’s second half. He’s a friend of Trip’s father who helps the pair on their way. As a male character, Pigsy, like Monkey, is modelled on an animal. He has the same core elements of physicality and nature. He experiences sexual desire, expressed in the kissing lips serving as his belt buckle, and briefly clashes with Monkey over their mutual interest in Trip. But Pigsy’s physical form is corrupted. He has a relationship with technology, but it’s the wrong type of relationship. It’s paired with and results in his degenerated physical form. Pigsy is short and fat – not a prime physical specimen like Monkey. He uses a grappling hook, unable to climb about or navigate the world through physical strength alone. He snuffles and snorts – he’s just gross. Pigsy is Enslaved‘s horror vision of an uncritical relationship with technology. It’s every stereotype about male gamers brought to life. Monkey still desires Trip, still desires some form of productive integration with technology and the digital world, but he’s also got Pigsy in his periphery. He wants to find a workable relationship without turning into a gross dork.

Thus the enemies to lovers narrative snaps into focus. Monkey desires Trip, but he doesn’t want to be too eager – he doesn’t want to seem like he’s pursuing her. He doesn’t want to be Pigsy. In that context his slavery headband serves as plausible deniability. He doesn’t want to help her, but he has to. He’s forced to. Dan Olson makes a similar point about compulsion in 50 Shades of Grey: “Ana rejects Christian’s gifts, which he then imposes on her. This allows the reader to indulge the dual fantasy of maintaining a sense of social propriety … while still enjoying all the material benefits”. In the same way, Monkey gets to pretend that he’s not actively interested in Trip. He retains a veneer of disinterest while enjoying the benefit of forced proximity. Enslavement is protective, freeing him to develop a meaningful relationship. That protective function is made explicit late in the game, when Trip briefly removes Monkey’s headband. He asks her to put it back on, enslaving himself again to preserve the developing relationship.

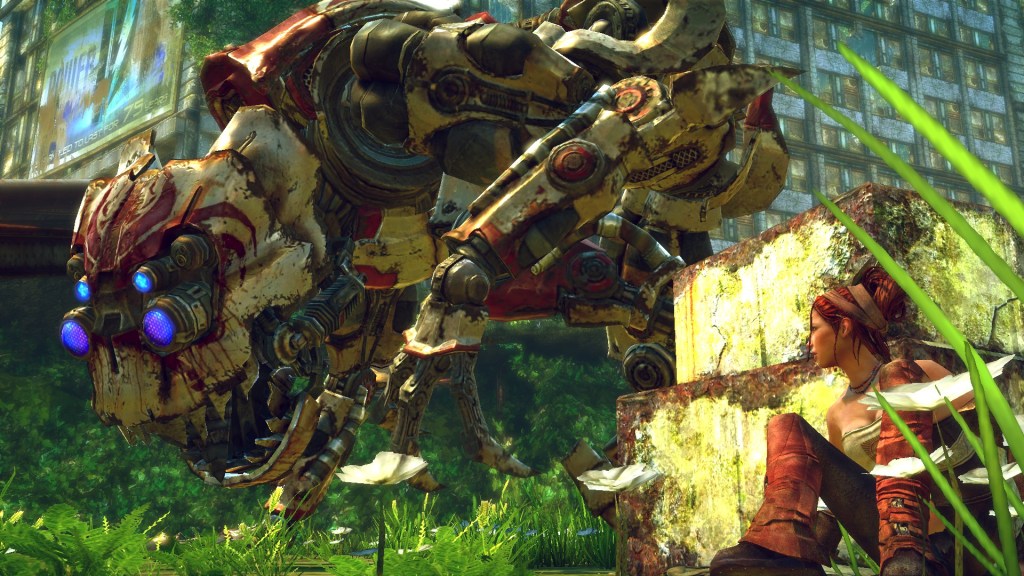

For all Monkey’s protesting, his relationship with Trip – with technology – is inevitable. The world has already fallen. There’s no going back. The technology is here, violently integrated into the landscape. It’s not civilizing or restorative: it’s just another part of the jungle. Certain mechs are shaped like animals, like the dragonfly drone mentioned before, or large, dangerous mechs like the so-called ‘dogs’, or the scorpion mechs that attack the heroes in the final mission. Monkey will succumb to technology. It’s only a question of what that transition looks like. In the game’s final scene, Pigsy dies heroically (sent off with a good death to make the audience happy that he’s gone), and Monkey and Trip meet the guy behind the slaver raids. It turns out that the slavers have been kidnapping people and hooking them up to a virtual world, protecting them from the harsh realities of the post-apocalypse by drowning them in memories of the olden days, Matrix-style. Monkey looks into one of the viewscreens and finds himself captivated. Colours flash before his eyes, flashing out equally at you the player. He’s absorbed. He sits on the edge, moments from transition into tech-slave, leaving Trip to save the day. She temporarily takes on some of the characteristics of Monkey, physically assaulting the lead slaver and tearing out the pipes that keep him alive. He dies, the visions shut down, and the slaves are released, coincidentally right before the player is pushed out of the completed game and back into the real world. There must be synthesis, the game insists. Technology has its hooks in us, in a forced and sometimes coercive relationship. We can’t get sucked into fantasies of the past or glittering digital visions. The jungle, the wasteland, the fallen city – this is where we live now. It’s not what it was before, and neither are we, but that doesn’t mean we have to lose ourselves. Back out into the wilderness, says Enslaved. You’re together now, and you’ll just have to make your way.