One of the annoying things about ‘narrative choice’ games, so-called, is that you’re often sort of guessing at the logic of the developers. You’re not just making a choice – you’re positioning yourself within a system with consequences that you might not be able to guess at. You’re trying to play the system rather than the situation. Occasionally the consequences are spelled out for you, as in the moralistic good/bad binary of BioWare games: the blue choice is good, and the red choice is evil. There are other, more diverse types of choice system too (we talked about them at length with the Vampire: the Masquerade visual novel Coteries of New York), but in each scenario you’re trying to guess what value the developers attribute to the choices they present you with. In the case of BioWare, the things they pitch to you as the good or evil choices often reflect more on the developers than on any objective statements of moral fact. In the infamous Legion loyalty mission in Mass Effect 2, for example, you’re asked to choose between genocide and brainwashing. You find a bunch of rogue robots: you can either rewrite their code, brainwashing them into supporting you, or you can make them all die. Which of those is the good option? According to BioWare, it’s the brainwashing. That’s not a moral assessment left up to you. It’s integrated into the systems and processes of the game, hard-coded with a moral value and a set number of hero points. You can have your own opinion, but the game doesn’t care. It’s already assigned value. All you can try to do is understand the system you’ve been placed in.

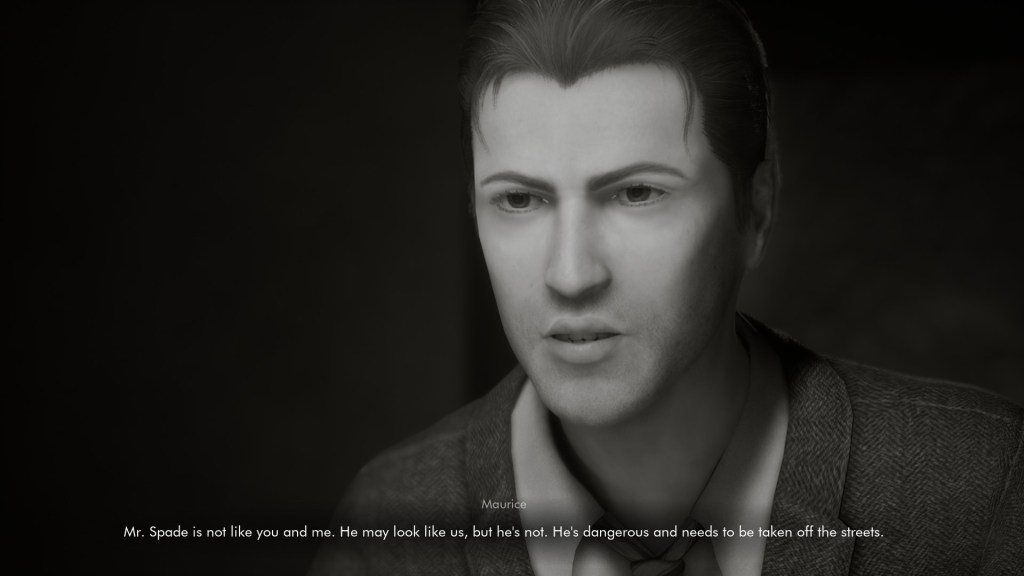

Lowbirth Games’ 2023 title This Bed We Made is a hotel murder mystery with a nosy maid and secret gay people. Set in the 1950s at the fictional Clarington Hotel, it has you play Sophie, a nosy chambermaid who makes the bed and rifles through suitcases. On the one hand it’s a game about voyeurism, like The Shapeshifting Detective or Beholder. It speaks to our desire to rake through other people’s lives. On the other, it’s a game about the dangers of investigation – the risks of the information you’re able to find. It starts as Beholder and turns into A Normal Lost Phone. I actually ended up with a relatively bad ending in This Bed We Made. That’s part of the reason we’re here – I made some poor choices and a bunch of people ended up dead or in jail. That’s my fault. I missed the signs. I didn’t register how the game evaluates your choices. As you move about This Bed We Made, you’re given the unusual option to throw away or destroy the items you come across. Early on, you discover one of the guests is stalking you. He’s taken photos of you cleaning other people’s rooms and trying on their perfume. There’s a bunch of incriminating evidence: you the watcher are in fact being watched. If you unlock this character’s safe, you’ll also find he has a gun. You can leave the gun and the photos in place, or you can throw it all away – and it seems pretty obvious that you should chuck it.

Through events like these, the game repeatedly tells you that it’s better to destroy the stuff you find. That’s the system that we’re working under. You should destroy those photos, or you’ll get found out. You should destroy the negatives in the safe as well, and get rid of the gun, unless you want your stalker to be armed. Other instances have lower stakes but carry the same message. There’s a spill near the lift early in the game. You’re taking a mop to the upper floors to clean up another mess – do you clean up the spill on your way? The consequences again tell you something about the system you’re working in. If you don’t clean the spill, one of your coworkers slips over on it. Get rid of it or someone gets hurt. The same pattern is repeated all throughout the game. You find lipstick insults scrawled on a senior colleague’s door: “Hypocrite – bitch”. You can find the offending lipstick in a friend’s locker. Do you wipe off the insults, or leave them there? If you leave them, your friend gets fired. The maintenance man similarly lets snow and rain into the manager’s office, in a protest against his behaviour. You find the mess – do you clean it up? If you don’t, the maintenance guy also gets fired. The game hammers the point home: always destroy the evidence. If you leave it there, someone’s getting in trouble. Your friend with the lipstick wasn’t even to blame – Linda, the senior colleague, put it on her own door to try and get your friend fired. Destroy the evidence, or people in power will use it to ruin everybody else’s life.

Although This Bed We Made doesn’t have morality points, there’s a consistent moral framing around your decisions. These choices are all structured in the same way – they play out the same. The game uses that framing to say something about evidence and punishment. The most pointed example is in the game’s central mystery. As you unpick the story, you discover two or three gay people hiding around the hotel. They are collectively running away – fleeing family, violence, institutionalisation. These characters have to keep their love secret. It’s the 50s – it’s not an accepting time. As the game comes to a close, a body is discovered in the hotel, and the police are summoned. You’ve gone through everyone’s rooms by this point, and you know about all the various incriminating papers and documents. You’ve read the secret gay love letters. Do you leave them, or do you destroy them? The game’s moral framing around all the other instances should lead you to a simple conclusion: destroy everything. Destroy the evidence, or people in power will use it to ruin everybody’s life.

For my part, I probably didn’t destroy as much as I should have. I didn’t fully process these systems until I’d finished the game – until I could look back and see the shape of everything. So a bunch of people got arrested for the wrong reasons. Most of them got arrested for being gay and/or previously institutionalised. I underestimated the dangers of investigation, the dangers of being able to get into the hidden details of people’s lives. And that’s slightly tricky, right – This Bed We Made is a game about being nosy. It’s a game about investigating. As the maid, you shouldn’t be seeing this information either. You shouldn’t be hunting for the code to break into a guest’s safe. Part of the tension of this game is that you’re invading people’s privacy, but you’re also the only person able to keep everyone safe – and in fact you keep everyone safe only by invading their privacy, by disposing of their secret gay love letters. The game is generally in favour of destroying the evidence, but it’s muddy on the more basic question of investigation. The identity of the actual murderer is even something of a secret ending. It involves some extra legwork that’s not really included in the central plot – you have to go out of your way to discover it. You have to take on the role of police investigator: not destroying evidence, in that instance, but uncovering it and reporting it to power. In that instance, the game isn’t even against the normal operation of law enforcement. It’s fine, the game says, as long as it’s pointed in certain directions.

As much as the game is a mystery, then, I don’t think we lose anything by knowing most of the events ahead of time. The more pointed exploration is in how the game unpacks these complicated ideas of investigation, power, and punishment. Who gets to know? Who gets to see, or not see? Who decides what information people should be privy to? You know you probably shouldn’t be snooping through people’s stuff. It’s not right to spy on people – and you yourself feel the anxiety and stress of being investigated when you discover all those photos in your stalker’s room. Probably none of this is good, the game says, but maybe sometimes it can be productive.

[…] The Ethics of Snooping in This Bed We Made(deathisawhale.com, James Tregonning) […]

LikeLike

[…] play like a mystery. It doesn’t have the mechanics of a mystery game – it’s not This Bed We Made. It’s a visual novel. You can sort of just tootle along and enjoy the music, and you’ll […]

LikeLike