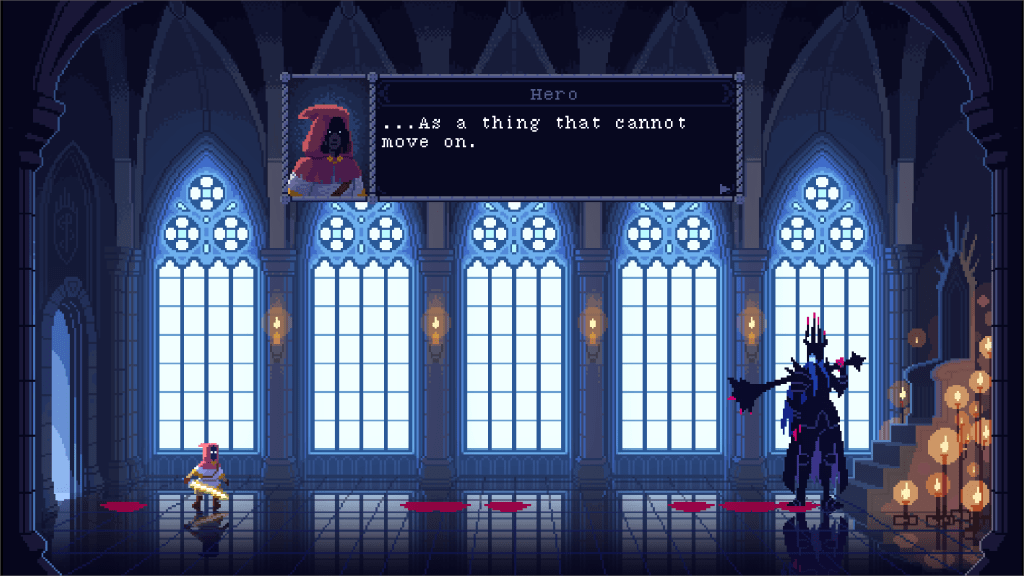

I feel like I always start to get a little uneasy this time of year. Winter’s setting in, and I’m not really motivated to do anything. I have a few little things floating around, essays I could write – there’s one on The Dark Queen of Mortholme, a sort of inverted Dark Souls game where you play a boss fight from the boss’s perspective. You’re miles more powerful than the hero, and you nail the little fucker, but he keeps coming back and learning a little more each time. It sounds fun and disposable – in practice, it’s a surprisingly thoughtful game about progress, change, inevitability. I have most of an essay planned on Aliens: Dark Descent, an XCOM-style game of squad tactics where you manage colonial marines through a nest full of Ridley Scott aliens. The pitch is that it’s not turn-based: it’s real-time, meaning you have these high-octane dramatic moments where you’re trying to coordinate your soldiers while a bunch of alien drones scream into the room and try to pull your spine out your ears. The actual essay was a Mark Fisher take on the disappearing future, the way that we’re still making stories revolving around the same franchises from forty years ago – in its depiction of a techno-corporate hellscape, Aliens: Dark Descent reproduces the conditions of its production. It’s just the bastard companies with their same old tricks.

I even have an essay parked on this ballet book from a few months back. I made passing reference in November to John Drummond’s Speaking of Diaghilev, a book about the ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev. Drummond has this whole thing about how Diaghilev was one of the last great arts directors, how everybody since has really just been an administrator – too much time in meetings, too much time spent on budgets. Drummond’s instinct is to idolise Diaghilev as this unshackled genius, but he keeps tripping over the actually quite serious shortcomings of the period. He oscillates back and forth between wistful daydreaming and a slightly surprised, apologetic recognition of the issues he’s just been airbrushing. There was no overtime in Diaghilev’s day! You’d just get a bit of wine and a picnic! But, yes, it is appropriate that the arts have unionised and stood for reasonable working conditions, and it is sobering how artists have been exploited, and I’ve tried to make that point myself in the past, but – gosh, weren’t things just easier back then? Drummond has a point about the problem of public funding, but the drapery distracts him from the core. He doesn’t have the clarity of vision to point towards neoliberalism as the culprit, with its chronic undervaluing of the arts. Instead he fixates on symptoms, blaming arts bureaucracy instead of the funding environment, and backing away from his own arguments. In one very funny passage about diversity quotas, he deploys his trademark style of making a point and then immediately retreating from it:

“Now the Royal Ballet … is obliged to respond to quotas such as the percentage of employees from ethnic minorities. Given that we live in a society where black classical dancers are very few in number, this has led to some curious appointments in other areas. I am not suggesting that the arts should not show an awareness of national policy, such as equal opportunities, merely that imposing and monitoring these policies puts the Arts Council and its clients in a very different relationship to that of the past.”

He stares into the face of racial disparity in ballet, with barely a flicker of thought as to why it might be happening, and then immediately trips on his dick. Why do we have diversity quotas when there aren’t even any black dancers? His immediate backpedaling is in turn utter nonsense: it’s good when the arts are aware of national policies, he says, but bad when those policies are imposed or monitored. We should be aware of the concept of equal opportunity, but not be held accountable for implementing it in any measurable sort of way. It’s just a bizarre set of arguments, poorly choreographed and honestly in places incoherent.

Anyway, all that’s to say I’m not lacking for things to write about. I have things to write about. I’m lacking the impetus. Partly it’s probably winter. Partly I was travelling for work last week and I’m still a little tired. Partly – I don’t know, I’m just not inspired. With some of the other things happening in my life, I had thought about closing down shop. Things have transpired such that I’ll keep going, but it was a question for a little while. I’m still sort of moving past that. Things are at a bit of a lull. We’re regrouping.

Anthony Burgess, who wrote A Clockwork Orange, has a short book of his favourite 99 novels. He wrote it in a couple weeks on commission for a Nigerian publisher, and he’s been very clear in interviews since that he really just did it for the money. I’m going to embrace the blog context today and write for the sake of writing, finish a piece just for the sake of getting something out there. It’s winter, and it’s cold, and I guess I’ll talk about what I’ve been reading.

The Anthony Burgess book is actually a pretty reasonable starting point. Covering novels from 1939 through to 1984, he picks roughly a couple for each year. All your classics are there (Catcher in the Rye, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Catch-22), as well as popular literary picks that are still renowned today (Pale Fire, French Lieutenant’s Woman, Gravity’s Rainbow). Some of the figures have probably declined in prominence (I’ve never met anyone who reads David Lodge novels), and some have naturally dated (I don’t know anyone who’s impressed by Philip Roth’s novel about wanking). Burgess wasn’t expecting everyone to agree with his choices, of course. He invited argument, saying he would be pleased by violent disagreement. Really that’s just a coded way to say he’s taking a punt on this list: it’s not a serious or systematic work, he’s just spouting some opinions. He invites criticism knowing there’s much to be criticized. He’s (correctly) imagining some professor snuffling into his breakfast over how some specific weird title didn’t get included.

Other than that, after finishing the Horus Heresy series, I’ve been reading some seventeenth century stuff. I’ve written before about Pilgrim’s Progress, by John Bunyan: I think there’s something to be said for the mythical fantasy quest of traipsing along in search of heaven. It has whimsy. That’s not the case for his other works. I cannot recommend Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners, his autobiography, or The Life and Death of Mr Badman, a sort of dull inverted Progress where it’s just some dude being evil his whole life and then going to hell. Both of them are not recommended. They are not fun to read. I had a few other little pieces on the go – Paradise Lost, by John Milton, and then two non-fiction books about the period: Seventeenth-Century English Literature by Bruce King, and The Seventeenth-Century Literature Handbook, by Marshall Grossman. I’m sort of circling around the period at the moment.

If you don’t know much about the seventeenth century, your most basic introduction goes like this. The sixteenth century is Elizabethan literature, which means Shakespeare. He’s quite late on – he’s writing from the 1590s through into to the early 1600s. The 1600s quickly become very dramatic. Charles I takes the throne in 1625, argues with Parliament for a bit, there’s civil war, and he’s executed in 1649. Oliver Cromwell takes charge and things get wild, but it all sort of settles down by 1660, with the restoration of Charles’ son, Charles II, as the monarch. It’s a very unstable time, with obviously a lot of conflict over the power of the church, the monarchy, and Parliament. The Protestant Reformation is underway, and England is switching between Catholic and Protestant almost every time there’s a new ruler. In the midst of all that, a bunch of people start coming up with new religious sects, striking out on their own. Methodists, Baptists, Anabaptists, some Presbyterians, Quakers, Diggers, Ranters – all of them trace their history back to this time. It’s generally a time for nonconformists and religious dissidents. Milton himself was a nonconformist – people still debate his exact religious beliefs, but as a point of reference he wrote pamphlets arguing that divorce should be legal for incompatible couples. If you don’t get along, if you’re not a good pair, he says, you should be able to get divorced. He was making those arguments four hundred years ago. John Bunyan was a nonconformist as well – again, if you’re not familiar with his story, he was a nonconformist preacher, locked up for twelve years for preaching without a license. It’s a period with a bunch of wild religious enthusiasm and free-thinking, it’s very fertile, and we get some of the classics of English literature – like Paradise Lost and Pilgrim’s Progress.

The following century is a very dull hundred years for literature. Not much happens in the 1700s. Music is good (Mozart, Beethoven, Bach), but literature is boring. The best they can do is Jonathan Swift, and he’s not even the main event. The big players are Alexander Pope (dull), Samuel Richardson (very boring), and playwrights like William Congreve, who wrote The Way of the World. It’s a wig period. That’s the best way to describe it to people. The 1700s is all people wearing wigs. Nothing good happens until the end of the century, when Wordsworth and Coleridge start publishing, and we move into Gothic and Romantic literature.

Really the 1600s are a time of hectic political and religious change. Everything seems like it’s up in the air. The power of the monarch slips, and we start on our merry way towards some form of democracy, towards some form of religious tolerance. Some of that’s reflected in the literature. You have these manic idiots getting themselves locked in prison for a decade over their preaching. Milton received a death sentence for supporting Cromwell. He went into hiding, and was eventually pardoned, but he could well have been executed before he’d finished writing the work for which he’s best known. I’ve written critically before on some of the writers from this period – I complained about Edmund Calamy, some preacher thrown out of the church, who essentially just railed against his fate, proclaiming that the country would crumble as long as his sect wasn’t in power. His self-righteousness is exhausting. At the same time, the confidence of the era is in some ways encouraging. John Bunyan happily went to prison for over a decade. Milton had a literal death warrant. They still wrote these glorious works. There’s an enthusiasm, a hurtling commitment. So much comes out of this time. It’s not good, but it’s generative. Maybe sometimes that’s as good as it gets.

[…] it sets out to disrupt those ideas. To raise just one instance, which we touched on last week (P is for Paradise, Pilgrims), Milton was a religious non-conformist. He disobeyed the institutional church, with its rules and […]

LikeLike

[…] published, including work that criticised the monarchy (see, for instance, previous discussions on Milton). Democracy rises along with the unshackled printing press, and we enter into an age of […]

LikeLike

[…] play. It’s interesting when they acknowledge that reflexively, playfully playing with play. The Dark Queen of Mortholme does this by inverting the Dark Souls experience, having you play a boss in a boss fight. The first […]

LikeLike

[…] – I mean, obviously, like when we were talking about Pilgrim’s Progress and Paradise Lost earlier in the year, this is just a bit of a yap. It’s list-making. Peter Mark Roget and me. […]

LikeLike

[…] see how we go, with everything else, but I enjoyed the seventeenth-century stuff last year (Pilgrim’s Progress, Paradise Lost and so on), and it might be nice to work more in that area. No promises, but […]

LikeLike