Dying Light 2 is the second game in Techland’s zombie parkour series. Released in 2022, it follows a formula set by the first Dying Light in 2015 and Dead Island in 2011: it’s a game about scavenging for resources and weapons in a weirdly cheery zombie apocalypse. Weapons degrade and break over time, combat involves a stamina bar, so you have to manage your energy rather than just swinging wildly, and you can craft supplies by scavenging for parts. The original Dying Light also introduced the parkour setting, which plays closer to Mirror’s Edge than Assassin’s Creed. The game has a day/night cycle, where the zombies, relatively placid by day, become creepy little demons at night. Each part of the cycle prefers a different playstyle: while you can fight zombies during the day, at night you should probably just run. That balance is also tilted by the degrading weapons and equipment – you can’t lounge around killing every zombie you see. Dying Light 2 was probably not quite as well-received as the first game, although for context, the first game at time of writing has 95% positive reviews on Steam, compared to 79% for the second. The first game is beloved, and the second game is well-regarded.

Tonally, Dying Light and Dead Island can be treated as a linked series of games. All of them are about the feeling of a zombie holiday. Dead Island is set on a tropical island; it’s a game about bikini zombies, zombies in Hawaiian shirts, juxtaposing gore and dismemberment against beach umbrellas as a way of pushing the saccharine markers of a resort holiday over into surreal nightmare. It’s a game about the emptiness and false cheer of the commercial environment, a critique borrowed from films like Romero’s Dawn of the Dead, with its zombie shopping mall, and reproduced in spirit by shows like White Lotus. In a similar vein, both Dying Light and Dying Light 2 have you play an interloper, somebody who enters into the zombie city as a visitor rather than a local. In the way they position the player, they are, again, resort games, showcasing a place that you visit rather than a place where you live. In the first game, Kyle Crane skydives into the city of Harran as a sort of CIA adventure tourist. In Dying Light 2, you’re told Villedor is the last city on Earth, but that’s not the context in which protagonist Aidan Caldwell approaches it. Aidan is looking for his sister, and passes through Villedor looking for clues. Despite the apocalypse, he’s quite happy wandering the wilderness – he enters into Villedor again as a tourist, as someone passing through, not as someone seeking refuge. Both games are about zombie holidays in urban playgrounds.

With that context, it’s interesting to consider the role of mess in Dying Light 2. In the first instance there’s the technical mess – glitches, bugs, crashes, and other weird little things. There’s one type of activity where you have to walk a power cable between sockets, navigating around obstacles in a complex chamber. You have a certain amount of cable length, and if you can’t reach the socket, you have to backtrack and try a different route. The cable, of course, is very unreliable, getting caught on nothing and stretching out in weird loops. In one underwater sequence, I got the cable caught on a barrel: even after I moved the barrel, the cable refused to retract, and stayed hooked around this non-existent point in space. Sometimes you can’t pick up the lootable gear in cupboards, because the game has spawned random junk on top of it; sometimes items on tables or counters get spawned inside or underneath the countertops. Technical issues are not alien to Techland, who had some bugs around Dead Island as well, but Dying Light 2 seems to have been particularly plagued, with a thousand bugs hit in a day one patch – no doubt part of the game’s weaker reception.

There are also strange inconsistencies in some of the dialogue. In a mission at the end of Act Two, ‘Broadcast’, the player climbs up a building to access the radio antenna at the top. At the start of the mission, the Peacekeeper leader, Jack Matt, sends you up with a troop of soldiers. One of his key lieutenants, Rowe, announces that he’s coming up with you. Jack Matt warns him to be careful and come back safe. On arriving on the higher levels of the building, all the soldiers are immediately killed by zombies, including Rowe. You climb on alone. Eventually Matt checks in on the radio, and the two of you exchange a couple words. You don’t tell him that Rowe is dead, or the soldiers. There’s no acknowledgement of what’s happened. He just asks if you’re hanging in there, and reminds you that the antenna is important. If, at the top of the tower, you give control of the antenna to Matt, he at least references Rowe being dead – so the game does at least confirm that he knows, if you pick that alignment option – but there’s no emotional resolution. The setup exchange between Matt and Rowe is wasted.

These elements are clearly unintended, but they resonate with more overt, intentional themes of mess throughout the game. The physical environment is a mess, as befits the apocalypse. Early in the game you try to get into a hospital: the doors are locked, but a bus has gone through the side of the entryway, so you climb through the bus to get inside. You dismember and deconstruct zombie bodies – human bodies – throughout the game: you hack and slash, explode, immolate, electrocute. You hack off arms and limbs, spray arterial zombie blood, spread guts and open skulls. Combat is hideously messy. Weapons are haphazard, constructed from bits of whatever. One is a cricket bat bound up with barbed wire. Elsewhere, nature intrudes across the city. Most rooftops feature uncontrolled natural growth – grass or greenery, flowers, ivy, wild beehives, sometimes even full trees. Even the floors themselves are often just filthy. There’s always stuff everywhere – discarded junk, matchbooks, bits of tarpaulin, papers, wire, random shirts, the plastic set of blisters that your medicine comes in. In one of the electrical stations, the control room is filled with empty water cooler barrels and a mini-fridge. Everywhere there’s stuff, but most of it’s not usable. This is true firstly on the level of game mechanic – there’s no available interaction for most of this décor – but more importantly as a diagnosis of the apocalypse. The world has plenty of stuff but no structure. All the pieces are there, but nobody knows how to bring it all together. Around the world you can find the relics of TV networks, train stations, electrical substations. The rooftops are covered with solar panels, and yet people are struggling to get clean water. It’s a mess.

The specific nature of Dying Light‘s power fantasy thus exists in opposition to Mirror’s Edge. In Mirror’s Edge, free running is used as a tool of resistance against encroaching state authority. The state builds a domineering architectural environment, which serves as a metaphor for control. Faith misuses the environment, using it in ways it was not meant to be used and thus (metaphorically) breaking free of state control. She doesn’t take the stairs: she vaults off the flowerbed and climbs over the railing. She runs free. Parkour in that game is a way to resist control. In Dying Light 2, parkour is a method for navigating mess. It’s the ability to use the built environment to achieve your goals. There exists in this game a superabundance of stuff. It’s not controlled or domineering – it’s wild, uncontrolled, run rampant. It is unmanageable to all parties. It’s a mess. Parkour is then the skill Aidan uses to navigate that mess. In Mirror’s Edge, free running is about breaking free from control. In Dying Light 2, it’s about cutting through the chaos. It’s about reasserting function rather than resisting it. All of the elements of city-building and competing factions tie into this framework – you’re supposedly trying to find your sister, but in a practical gameplay sense most of your effort goes into rebuilding the city of Villedor. You reactivate the substations, clear out the train lines. You bring the city back to life, and assign control of it to one of the main factions – either the Peacekeepers or the Survivors. You have the ability to navigate mess; you give structure in an unstructured world.

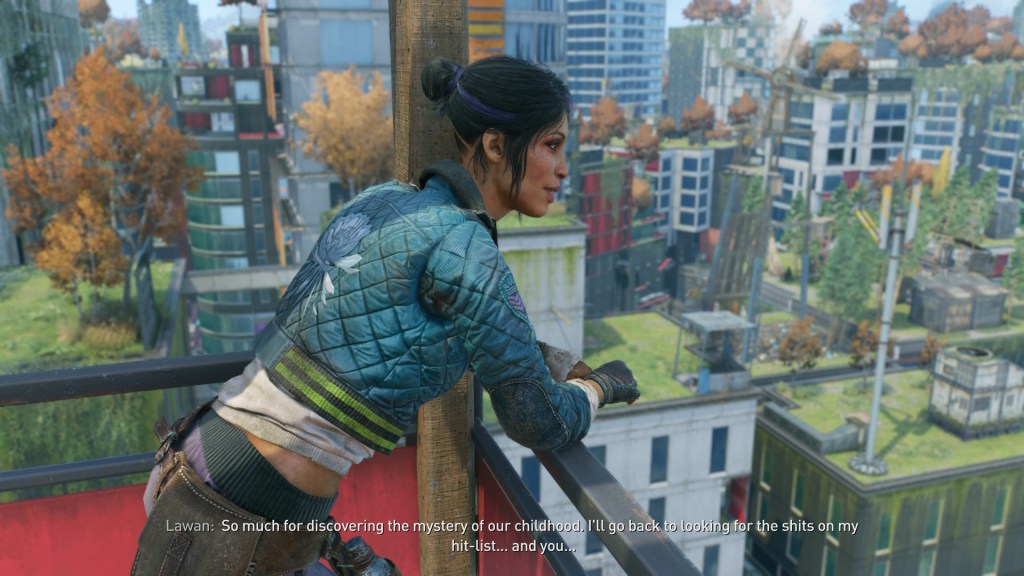

Given all of that, the structural problem with Dying Light 2 (or one of the problems, I guess) is how that process of rebuilding the city clashes with the zombie holiday. In an early E3 trailer in 2018, Dying Light 2 was pitched as this complex city-builder – all of the zombies and parkour from the first game, but the city would grow and evolve. Decisions to side with one faction or the other would have unexpected, negative effects. The Peacekeepers would become an aggressive military force, while the vulnerable Survivors would attract bandits. Decisions would have consequences. In reality, the game is set in a resort. The question of city alignment isn’t really concerned with the wellbeing of the people of the city, or the philosophy of government, or the unexpected nature of cause and effect. It’s mostly about your perks. Depending on which faction you lean towards, Peacekeepers or Survivors, you’ll unlock different perks, which either help you navigate around the city or help with combat. It’s just another aspect of the resort – do you want to go snorkeling, or do you want to go on the jet skis? The game architecture is built around keeping you entertained moment to moment. The promise of a messy, complex city-builder, with fragile alliances and complicated relationships, flattens into a zombie holiday. It keeps you moving, but there’s very little depth. The characters are background props rather than fully fleshed out people. Their integrity, the fact of their existence, is airbrushed into something manageable and aesthetic – a question of wallpaper. You still cut through the mess, but not really with any intention. You’re just on holiday.

[…] they would have weight and texture, material density. Compare them especially to the buildings in Dying Light 2, the zombie parkour game we’ve been discussing recently – those buildings (pictured on […]

LikeLike